This is the first in a series of four posts on the American Civil War. In the first three posts, I will describe the three combat arms used during the Civil War to accomplish military objectives. These roles include: cavalry, infantry, and artillery. In the final post of the series, I’ll describe the role of the Civil War chaplain. With each post, I’ll also include the story of a Spaulding family member who served during the Civil War in each of these roles.

The Cavalryman

The Civil War saw extensive use of horse-mounted soldiers called Cavalry. Cavalry units were vital for conducting reconnaissance missions and conducting raids behind enemy lines. Cavalry forces fought principally on horseback, armed with pistols and sabers. Calvary was expensive. The cost to equip a cavalry regiment was nearly twice the amount of an infantry regiment.1 Why? One word – horses!

Reconnaissance missions were one of the most important roles of the cavalry. The cavalry’s agility and mobility made them ideally suited to be the eyes and ears of the field commander. Additionally, cavalry units had the firepower to quickly probe the enemy for weak points, set ambushes, and rapidly flee before enemy reinforcements could be rallied.1

Here’s a sample of how a Civil War cavalry regiment was organized: The First Regiment, Vermont Calvary was led by Colonel Lemuel Platt. His second in command was Lieutenant Colonel George Kellogg. The First Regiment, Vermont Cavalry consisted of ten companies each led by a Captain. The enormity of the logistics operation to move a force of this size from Vermont to the battlefields in the south was astonishing. After the First Regiment, Vermont Calvary was mustered into service in November 1861, it required 153 railroad cars to move the regiment’s 2,000 men, horses, and supplies south to Virginia.2

Private Henry C. Spaulding

Henry Charles Spaulding was the only son of my 4th great-uncle Otis Spaulding. Henry was born in Ohio in 1844. According to the 1860 census, Henry, at age 15, lived at home with his parents in Windsor, Vermont and was recorded in the census as a farm laborer. The following year on April 12, 1861, the Civil War broke out when Henry was 16.

On Christmas Day in 1863, at age 19, Private Henry C. Spaulding joined the Union Army and mustered into Company F of the First Regiment, Vermont Cavalry. Company F was led by Captain Josiah Hall.

Private Henry Spaulding’s cavalry unit engaged in a battle near Mechanicsville, Virginia, on March 1, 1864. The following day in a skirmish at Piping Tree near Cold Harbor, Virginia, Private Henry Spaulding was reported as missing in action. It was later determined he was captured by Confederate troops and taken prisoner on March 2, 1864. Private Henry C. Spaulding and others captured that day were first held prisoner in Richmond.

Letters Home

In late 2022, I visited the National Archives in Washington, D.C. and accessed the Civil War service record of Private Henry C. Spaulding. Holding those original documents from nearly 160 years ago was a surreal moment. As I carefully flipped through the pages of Henry’s military record, I came across three letters he had written home to his parents Otis and Azuba Spaulding (my 4th great aunt and uncle). The paper of these 160-year-old letters was thin and fragile. The tattered edges of the paper were stained with the mud of the Virginia soil. These were the original letters – not copies.

One letter in particular was penned on February 14, 1864, just 16 days prior to Henry’s capture. It was written from Stevensburg in the central part of Virginia, just east of Culpeper, 80 miles northwest of Richmond. As you read the words from Henry’s letter below, you get a first-hand glimpse into the day in the life of a Civil War soldier. Little did he know this would be his last letter home.

Stevensburg, Feb. 14th, 1864

Dear Father and Mother,

I received your letter yesterday and was glad to hear from you. I am well and enjoy myself first rate. I think my life is about as safe here as it would be up in Vermont although there is quite a number of the boys are sick here and Michael Lynch of Ludlow died a day or two ago. I have been on picket for 3 days past – came in today. The Johnny’s are deserting every night. There was ten came over while I was out – 2 orderly sergeants and 8 privates. They was Louisianans and one of them had a lot of names of some more that was coming into our lines as soon as they got down on picket. Our posts and the Rebs are not more than 30 rods a part. Their posts are right opposite ours. They did not stand only nights while I was down there. They think that the war will not last over one year. They think there will be pretty hard fighting this summer and they have got a large army and can raise a good many more. They get 11 dollars a month and the money is not good for much they said. Flour was $200 a barrel and whiskey $10 a canteen full. One of them had 75 dollars confederate money with him and they are not allowed to pass any of our money or take any away from our men when they take them prisoners. They are dressed in grey. Had very good clothes except pants – they was rather ragged and was smart looking men. Well I don’t know as I can tell anything more about them so I will commence on something else. How did the mare loose her colt, get east or in to the snow? I am going over to see Page tomorrow if I can get a pass. I think I can. What was the matter with Ms. Heselton and Hemensay’s girl and is Oserz better – has Georgia got well? I have had a sore throat and a cold and could not speak loud for a day or two but am all right now. Oh I was vaporated a few days ago but it has not worked any yet. I don’t think it will. I am glad you are getting the timber along so well for a barn. Have you got the wood all up yet? And are you going to have hay enough to go through winter? We don’t have a might of hay for our horses. Nothing but corn and oats. I don’t think of much more to write this time. I got the stamps all right and a letter from Melissa and 2 from By and Danad. They all came in the same day. Tell Melissa I will answer them soon. How does Mabel get along? Is she full of mischief as ever? I dare got 1 or 2 more letters to write so I will close. Write soon and send a paper.

From your son away out in Virginia,

H.C. Spaulding

Andersonville Prison

On May 31, 1864, Private Henry C. Spaulding and other Union soldiers were loaded aboard a cramped boxcar in Richmond and moved by railway to Camp Sumter, a gruesome Confederate stockade prison infamously known as Andersonville in southwest Georgia.

Andersonville was dreadful in its appalling living conditions. Union prisoners suffered not only from their battlefield wounds, but also from rampant disease in the camp. Food was scarce, and many men were but mere skeletons as they died of starvation, dysentery, and other parasitic diseases. Ten miles south of Andersonville, citizens of Americus, Georgia, complained of the stench permeating from the prison camp.

By August 1864, the number of Union prisoners held at Andersonville grew to over 30,000 in a camp designed to house no more than 10,000.3 In reality, there was no “design” at all. There were no shelters, no beds, no toilets, and very little food. The only drinking water available was what the men could catch with their clothing when it rained. The soldiers’ uniforms they arrived in were the only clothes they wore during their entire imprisonment at Andersonville. They washed those clothes in a swamp at the center of the camp. And those were the clothes that many would be buried in.

Conditions at Andersonville rapidly deteriorated after the camp opened in early 1864, as unsanitary conditions fueled by malnutrition and disease led to the death of nearly 13,000 men.3 The 900 Union soldiers dying each month were buried in mass graves outside the perimeter of the POW camp.

Knowing his days were numbered, and his illness severe, Henry painstakingly cut a hole in the center of his Bible and placed his pocket-watch inside. He then bribed a Confederate guard to send it home to his family in Cavendish, Vermont.

On August 12, 1864, Private Henry C. Spaulding became one of those tragic stories of Andersonville, when he died of “scorbutus” at age 20. Scorbutus is a medical term for scurvy. It was a slow, agonizing death resulting from prolonged malnutrition, anemia, and hemorrhages of the skin. Henry survived for 73 agonizing days at Andersonville. Union soldiers like Private Henry C. Spaulding, who died at Andersonville, were buried shoulder-to shoulder in mass grave trench lines of 100-200 bodies.

In July 1865, three months after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, an expedition of soldiers accompanied by American Red Cross founder, Clara Barton, traveled to Andersonville. Their mission was to identify the shallow graves of the Union dead and transform that dreadful place into the Andersonville National Cemetery. Private Henry C. Spaulding was interned in grave 5421 at Andersonville.

August 12, 1864 was a profoundly sorrowful day for Otis and Azuba Spaulding as they mourned the loss of their only son. Nevertheless, at the same time their hearts were filled with pride for their brave young son who went to war to preserve the Union they so loved.

Fortitude

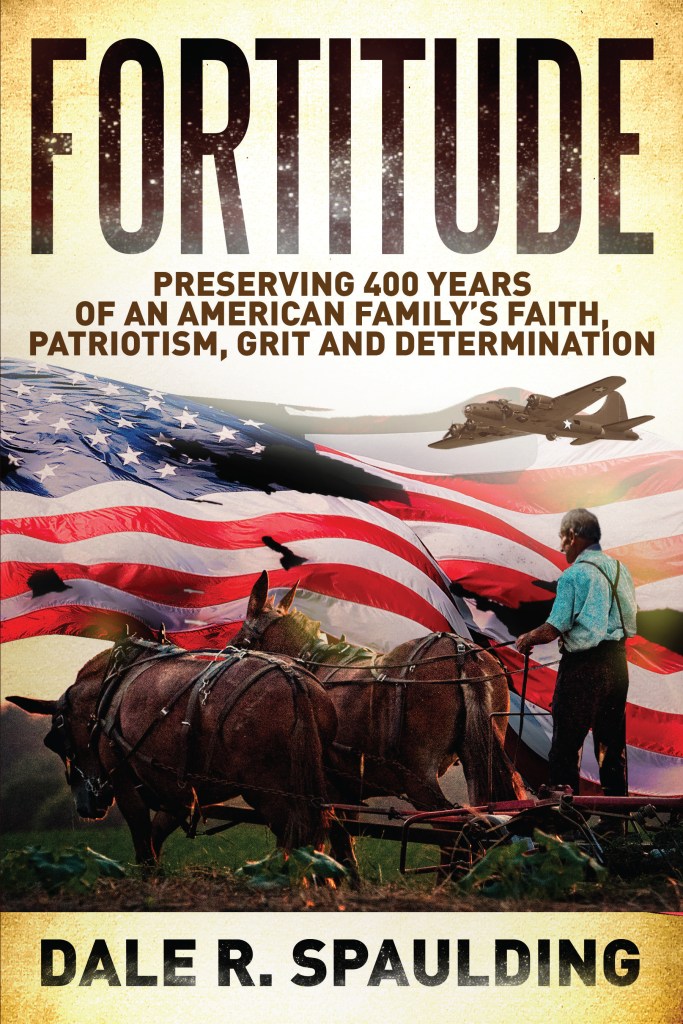

It’s stories like that of Private Henry C. Spaulding that drove me to name my book Fortitude. A person of fortitude has the strength of mind to enable them to face into danger or adversity with courage. Fortitude is the story of Private Henry C. Spaulding.

If you’d like to read more of the compelling story of Henry C. Spaulding and other patriots that have been part of the fabric of America since its inception, please check out my book Fortitude: Preserving 400 Years of an American Family’s Faith, Patriotism, Grit and Determination HERE.

NOTES

- Wikipedia. Cavalry in the American Civil War. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cavalry_in_the_American_Civil_War on May 12, 2023.

- Greenleaf, W. First Regiment Cavalry, 214. Accessed from https://vermontcivilwar.org/rr/1st_Cavalry.pdf on May 13, 2023.

- National Park Service. History of the Andersonville Prison. Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/camp_sumter_history.htm on May 13, 2023.

- Featured Image: CivilWarCavalry.jpg. Pxfuel Royalty free stock photos. Accessed from https://www.pxfuel.com/en/desktop-wallpaper-auudq on May 13, 2023.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A really great in depth overview! The cavalry units in the civil war don’t get as much attention as they deserve. Thank you for your family’s service to our country!

LikeLike