This is the third in a series of four posts on the American Civil War. In this series, I describe the three combat arms used during the Civil War to accomplish military objectives (cavalry, infantry, and artillery). With each post, I also include the story of a Spaulding family member who served during the Civil War in each of these roles.

In the final post of the series, I’ll describe the role of the Civil War chaplain. You can read the first post on the Civil War cavalryman HERE and the second post on the Civil War infantryman HERE.

The Artillery Unit

The basic unit of field artillery in the Civil War was the battery, which usually consisted of six guns. The light (mobile) artillery’s purpose was to support infantry units on the battlefield. Each gun (piece) was operated by a gun crew of eight, plus four additional men to handle the horses and equipment. Each piece was commanded by a sergeant. Two guns (plus limbers and caissons), operating under the control of a lieutenant, were known as a “section” and consisted of 16 men and 24 horses. A battery of six guns were commanded by an Army captain and consisted of 70-100 men. Artillery brigades, composed of five batteries, were commanded by an Army colonel.2

“A battery of field artillery is worth a thousand muskets.”

General William Tecumseh Sherman, Union Army (~1863)

The Crew

Eight cannoneers were required to fire an artillery field piece. Five members of the crew were stationed at the gun (the gunner and cannoneers 1, 2, 3, and 4). The gunner (a Sergeant) gave the commands and aimed the weapon. Cannoneers 1-4 loaded, cleaned, and fired the gun. Cannoneer 5 ran ammunition from the two-wheeled limber (cart that carried the ammunition chest). Cannoneers 6 and 7 prepared the ammunition and cut the fuses.3

The Commands

The positioning of the eight cannoneers and commands given to fire an artillery piece were as follows:4

Load: Cannoneer 1 slides a dampened sponge down the barrel to extinguish burning embers from the previous firing. Cannoneer 3 tends the vent by placing his leather-covered thumb on the vent hole to ensure that no air passes through the opening. Cannoneer 5 brings the charge from the limber chest to Cannoneer 2. When Cannoneer 1 finishes sponging the piece, he turns the staff around and taps the muzzle indicating he has finished. After Cannoneer 2 hears the tap, he removes the charge from the pouch and places it in the muzzle. Cannoneer 1 rams the charge by pushing the cartridge to the breech of the cannon. Cannoneer 3 removes his thumb from the vent, takes a priming wire from his pouch and inserts it through the vent making a hole in the cartridge powder bag.

Aim: The Gunner aims the gun by depressing or elevating the barrel as necessary, and traversing the piece right or left as needed to acquire the target.

Ready: Cannoneer 3 removes the priming wire. Cannoneer 4 fixes the lanyard to the friction primer and inserts the friction primer into the vent. Cannoneer 3 holds the lanyard maintaining eye contact with Cannoneer 4 as he takes up the slack on the lanyard. Once Cannoneer 4 has fully extended the lanyard, he will turn his head away from the gun and maintain eye contact with the Gunner for the next command.

Fire: The Gunner gives the command to fire. Cannoneer 4 pulls the lanyard causing the friction primer to spark sending a flame into the breech of gun igniting the main powder charge and sending the round downrange.

During the Civil War, a well-trained artillery crew could move through these steps above and fire their artillery piece 3-4 times per minute. Picture that in your mind and let that sink in for a moment.

The Ammunition

The typical Civil War artillery battery would carry a combination of the following artillery rounds into battle:3

Shot: A cast iron ball with no explosive. Shot ammunition was used against enemy troops in formation or fired at buildings and other structures.

Shell: A round, hollow projective with a powder-filled cavity. The shell was fused and exploded in the air into 5-10 fragments.

Spherical Case: A hollow shell packed with powder and 40-80 musket balls that exploded in all directions.

Canister: A thin metal can holding 20+ lead or iron balls packed in sawdust. The canister round turned the artillery piece into a giant shotgun as the container ripped open at the muzzle when fired scattering iron balls upon incoming enemy troops. Double canister was ordered when the enemy was at close range with devastating effects.

The Story

My third great-uncle, Henry A. Spaulding, born in 1830, was the oldest child of my third great-grandparents Addison and Nancy Spaulding. Henry is the older brother of my third great-uncle, Private Oscar Spaulding, who served with the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cedar Mountain in 1862.

In 1860, Henry purchased a flatboat in his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts, loaded it with provisions, traversed east on the Merrimack River in Lowell for the Atlantic Ocean, and headed south along the U.S. coastline for New Orleans. Poor Henry was at the wrong place at the wrong time. War was on the horizon in late 1860, and Henry’s boatload of goods was ripe for the taking. Newly formed Confederate forces seized Henry Spaulding and his boat while he was in New Orleans.

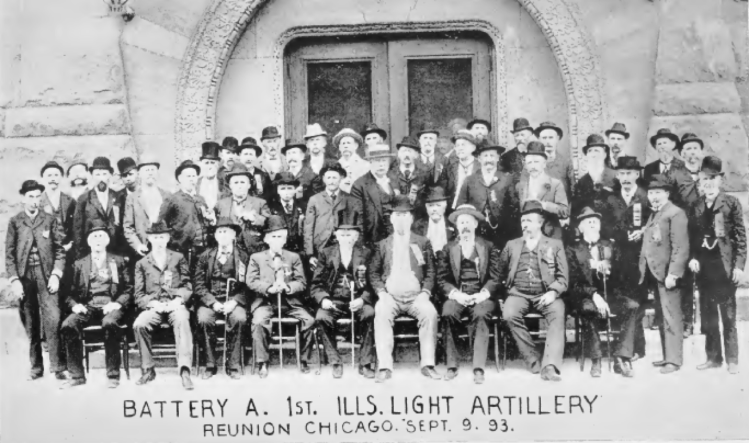

Somehow Henry escaped and made his way up river to his younger brother William Sidney Spaulding’s (my 2nd great-grandfather) home in Rock Island, Illinois. Infuriated with the “southern hospitality” he received in New Orleans, Henry then headed for Chicago to enlist in the Union army, to perhaps garner a little revenge. On August 25, 1861, Private Henry A. Spaulding mustered in for duty with Battery A, 1st Illinois Light Artillery (his unit is pictured above).

Private Henry A. Spaulding saw plenty of action during his three-year service in the Civil War – none more relentless than the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862. In an after action report from the first day at Shiloh, Lieutenant Peter P. Wood, Battery A, 1st Illinois Light Artillery documented that his unit engaged the enemy for seven successive hours firing 838 rounds of ammunition. Wood reported casualties of four men killed and 26 wounded with a loss of 48 killed or disabled horses. Think about those numbers for a moment – as this was just one day from one battery out of the numerous artillery, cavalry, and infantry units that fought at Shiloh.

Private Henry A. Spaulding completed his three-year tour of duty on August 24, 1864. His military service record states that he was discharged near Atlanta, Georgia, by reason of expiration of term of service. He then returned to his hometown in Lowell, Massachusetts thankful that he survived the war but deeply saddened that his younger brother, Oscar, did not.

The Sacrifice

Take a moment to think what life was like for your family’s ancestors who fought in the Civil War. My third great-uncle, Private Henry A. Spaulding, joined the Union Army in 1861. He left the comforts of home and spent three years traveling nearly a thousand miles, moving the guns of Battery A, 1st Illinois Light Artillery onward to the next fight.

Imagine the painstaking task of repositioning those ironclad cannons through mud-laced terrain for miles on end only to then go into battle after minimal rest at night. Men like Private Henry A. Spaulding endured bitter cold winters and scorching hot summers day after day after day for three agonizing years. This was the life of the Civil War artilleryman.

Private Stephen T. Spaulding, a distant cousin of mine from the past, spoke of the life of a Civil War artilleryman in comparison to his own experiences with the 140th New York Infantry in a letter home to his sister Esther on January 17, 1864. He was responding to the news that his sister’s husband Aaron had joined the 1st New York Light Artillery. He wrote:

“I pity, as you do not wish to spare him, but it was the right way for him to do, as he would have to go perhaps anyway and he had better go where he pleases and get pay for it in the bargain. He, I suppose, had rather go in a battery, but I have seen enough of fighting so I would rather go in infantry sooner than any other branch of service. The cavalry and batteries have done weeks of fighting when infantry was not engaged at all, but the danger in an all day’s fight is much greater in infantry than artillery, and in a charge then the infantry suffer most. You will see many lonesome hours, but think of the cause he is fighting in and be happy and proud. May the giver of every good and perfect gift, grant us all a happy meeting. May I and Aaron live to enjoy the blessing we are fighting to gain.”5

Private Stephen T. Spaulding, Union Army (1864)

Fortitude

It’s stories like that of Private Henry A. Spaulding that inspired me to name my book Fortitude. A person of fortitude has the strength of mind to enable them to face into danger or adversity with courage. Fortitude is the story of men like Private Henry Spaulding of Lowell, Massachusetts.

If you’d like to read more of the compelling story of Henry and other patriots like them that have been part of the fabric of America since its inception, please check out my book Fortitude: Preserving 400 Years of an American Family’s Faith, Patriotism, Grit and Determination HERE.

NOTES

- Featured Image: Civil War Era Artillery Demonstration is in the public domain and was accessed from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Civil_War_Era_artillery_demonstration,_Springfield_Armory,_Springfield,_Massachusetts.jpg on July 19, 2023.

- Wikipedia. Field Artillery in the American Civil War. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_artillery_in_the_American_Civil_War on July 19, 2023.

- ThomasLegion.net. American Civil War Artillery Organization. Accessed from http://www.thomaslegion.net/americancivilwarartilleryorganization.html on July 20, 2023.

- National Park Service. Firing the 12-pdr Napoleon. Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/vick/planyourvisit/firing-the-12-pdr-napoleon.htm on July 20, 2023.

- Roth, Richard W. (2020). Away Amongst Strangers. Pennsylvania: Mechling, pp 143-144.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “A Civil War Artilleryman’s Story”