May is an introspective month on the calendar each year in the United States as it concludes with Memorial Day. As I reflect on Memorial Day this year, my thoughts take me back to World War I. This month’s post wasn’t easy to write, and may not be comfortable to read, but it’s a story that must be told – the story of the repatriation of the bodies of war.

The reality of World War I was that, tragically, after particularly deadly firefights, the bodies of battlefield heroes remained for extended periods of time entrenched in the mud where they breathed their last breath. Others were identified by burial details following the battle and interred in temporary graves. After the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918 to end World War I, the ominous work began to clear battlefields of destroyed military machinery, and to attempt to retrieve the corpses of the fallen who were missing in action.

Repatriation Defined

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, repatriation is defined as the “act or process of restoring or returning someone or something to the country of origin, allegiance, or citizenship”.1

The repatriation of American World War I causalities began with relocating fallen soldiers from temporary burial locations to purpose-built cemeteries. This task was complicated by the condition of these former battlefields. The trench warfare of World War I left in its wake thick mud, collapsed underground tunnels, unexploded ordinance, and bodies decayed beyond recognition. Exhuming the bodies of fallen patriots was a traumatic task for the men assigned to recovery and burial details.

Repatriation Stories

Following World War I, the U.S. government sent over 70,000 questionnaire cards to the next of kin of the fallen to determine their wishes regarding the remains of their loved one. The first question asked if they desired the remains to be brought back to the United States. If remains were to be brought back, they were asked if they wanted their loved one interred in a national cemetery. If they did not, they were asked to provide an address and contact information to where the remains should be shipped. By January 1920, over 63,000 questionnaire cards were completed and returned.2

If you are a follower of my blog, you know that I write about history and I typically give examples of how Spaulding family members intersected those moments of history. This post contains the stories of several Spauldings who were killed in action during World War I. One Spaulding’s remains were repatriated back to the United States; the four others were not. Those brave Spauldings remain buried in Europe where they gave their last full measure of devotion to our country.

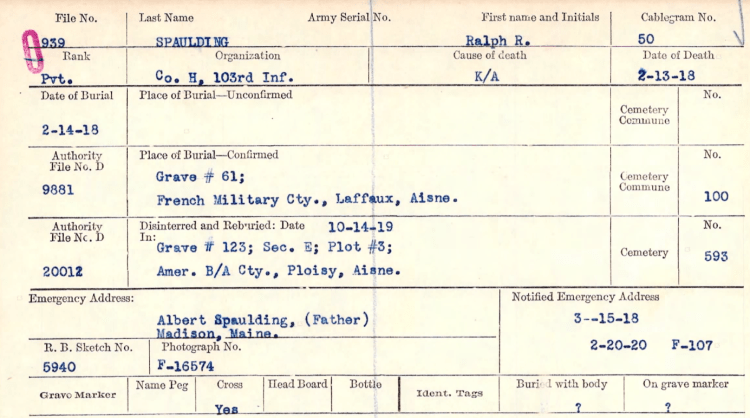

Private Ralph R. Spaulding

Born in 1896, PVT Ralph Spaulding was from Maine. In World War I, PVT Spaulding was assigned to Company H of the 103rd Infantry Regiment, 52nd Infantry Brigade, 26th Infantry Division (“Yankee Division”) of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).

In the winter of 1918, PVT Spaulding’s unit was operating in the Chemin Des Dames area north of the Aisne River in France. On February 13, 1918, PVT Ralph Spaulding became the 26th Infantry Division’s first combat death when he was killed by an exploding enemy shell.3 PVT Spaulding’s repatriation journey then began – a journey that would take three years to complete.

Ralph’s Repatriation Timeline

- 13 Feb 1918: Killed in Action.

- 14 Feb 1918: Buried in French Military Cemetery at Laffaux, Aisne in Northern France.

- 14 Oct 1919: Disinterred and Reburied in American/British Cemetery at Ploisy, Aisne.

- 19 Mar 1921: Disinterred for preparation and shipment to the U.S.

- 01 Apr 1921: Body arrived at Antwerp, port city of Belgium.

- 22 Apr 1921: Body shipped to U.S. aboard U.S. Army Transport (USAT) Somme.

- 06 May 1921: Body arrived at Hoboken, New Jersey.

- 12 May 1921: Body shipped to Madison, Maine (Ralph’s hometown).

- 14 May 1921: Body received at destination by Austin I. Williams. Austin was a carpenter married to Ralph’s sister, Jennie M. Spaulding.

- May 1921: Ralph was buried in his final resting place at Forest Hill Cemetery in Madison, Maine.

While PVT Ralph Spaulding’s remains were repatriated back to the United States for burial in his hometown in Maine – other Spaulding men killed in WW1 remain interred in Europe. Here are but a few of their stories.

Sergeant Bernard F. Spaulding

SGT Bernard Spaulding was from Brooklyn, New York. He served with the 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division. He was killed in action on October 3, 1918. SGT Bernard Spaulding is buried in Plot D, Row 41, Grave 20 at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France. Most of the 14,246 buried there were killed during the Meuse-Argonne offensive in World War I.4

Private John Spaulding

PVT John Spaulding was from Georgia. He served with the 167th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division. He died on July 26, 1918. PVT John Spaulding is buried in Plot B, Row 18, Grave 27 at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in France which holds the remains of 6,013 American war dead from World War I.5

Private First Class Leonard T. Spaulding

PFC Leonard Spaulding was from Etna, New York. He served with the 309th Infantry Regiment, 78th Division. He was killed in action on October 17, 1918. PFC Leonard Spaulding is buried in Plot C, Row 25, Grave 39 at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France.

Second Lieutenant Albert G. Spalding, Jr.

Born in 1891, Albert Goodwill Spalding, Jr. was from Chicago, Illinois. Now that name may be familiar. Why? Because Albert was the son of Albert Goodwill Spalding, founder of Spalding Sporting Goods.6

Spalding, Jr. was working at the Paris office of Spalding Sporting Goods when World War I broke out. He promptly traveled to England and enlisted on August 29, 1914. PVT Spalding was assigned to the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards regiment of the British Army.6 The Coldstream Guards were among the first British regiments to arrive in France after Britain declared war on Germany. In subsequent battles, they suffered heavy losses included many of their officers.7

In December of 1915, LCPL Albert C. Spalding obtained his commission as a second lieutenant after meritorious conduct under fire during the Battle of Loos on the western front in France. Seven months later, 2LT Spalding was killed in action on July 1, 1916 at age 25 on the opening day of the Somme Offensive while serving with the 10th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers of the British Army.6

2LT Albert Goodwill Spalding is commemorated at the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme in France. This war memorial records the over 70,000 missing or unidentified British and South African serviceman who died at the Battles of the Somme between 1915 and 1918 who have no known grave.8

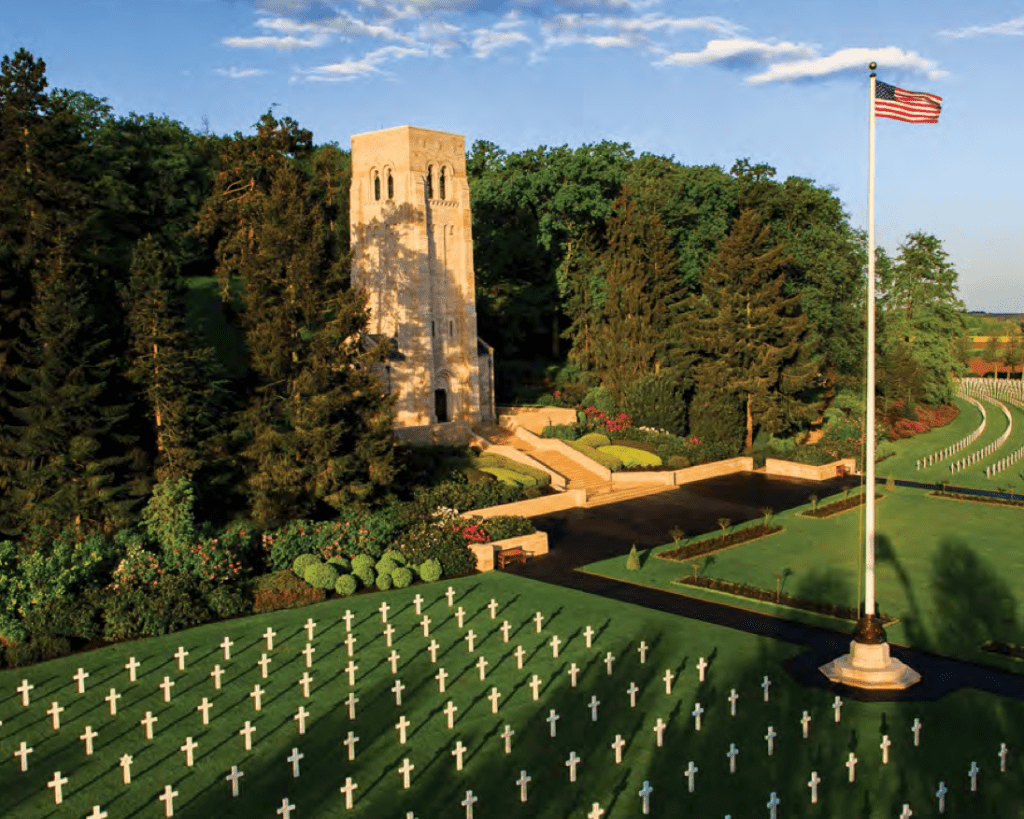

The ABMC

Following World War I, the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) was established in 1923. The ABMC is the guardian of America’s overseas cemeteries and memorials. These 26 American military cemeteries and 27 memorials and monuments are located in 16 foreign countries. Like Arlington National Cemetery, ABMC locations are meticulously maintained to honor our country’s military.9

U.S. General of the Armies, John J. Pershing, was elected chairman of the ABMC in 1923 serving in that role until his death in 1948. General Pershing commanded the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during World War I.10

During World War I, over 116,000 Americans lost their lives in Europe. The critical task at hand was to determine the desires of Americans who wished to have the remains of their fallen military family members repatriated home for interment in a national or private cemetery. Or, to choose interment in an ABMC cemetery overseas. Approximately 30% of families elected to have their loved ones buried with their brothers-in-arms overseas.9

Each World War I grave at overseas ABMC cemeteries is marked with a white marble headstone. Unidentified servicemen’s headstones are marked with:

HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY AN AMERICAN SOLDIER

KNOWN BUT TO GOD.

Gold Star Pilgrimages

During the 1920s, the Gold Star Mothers’ Association lobbied for a federally sponsored pilgrimage to Europe for mothers with sons buried overseas. In 1929, Congress enacted legislation to arrange for pilgrimages to European cemeteries for mothers and widows of the servicemen who died during the war. The Office of the Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army determined that 17,389 women were eligible.11

Between 1930 and 1933, eligible women sailed to Europe to visit the graves of their sons and husbands. The U.S. government paid all expenses for these Gold Star Pilgrims. The local cemetery superintendent gave each pilgrim a grave locator card, and cemetery staff guided each woman to the gravesite. The guide then gave the women flowers or a wreath to put on the grave and took a photograph. Although the overall trip was somber in nature, the women were afforded time to visit the sites in Paris before traveling back to the United States.12

By the time the project ended in 1933, the Gold Star Pilgrimage provided the opportunity for 6,693 women to visit their loved ones graves in Europe.12

Final Thoughts

This Memorial Day, I encourage you to visit a national cemetery to pay respects for those who served our country with honor and courage. When I lived in Virginia, I oftentimes visited Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day weekend. Now that I live in North Texas, I plan to visit the Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery this Memorial Day. You can find your closest National Cemetery HERE.

lf while visiting a national cemetery, you find a serviceman killed during World War I (1914-1918), you now have a glimpse into their repatriation journey!

NOTES

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Repatriation noun. Accessed from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/repatriation# on February 7, 2024.

- Ruane, M. 2021. Washington Post. After World War I, U.S. families were asked if they wanted their dead brought home. Forty thousand said yes. Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/05/31/world-war-i-exhumed-memorial-day/ on March 7, 2024.

- Bratten, J. An Unlikely War Poet: A Doughboy From Maine. Accessed from https://armyhistory.org/an-unlikely-war-poet-a-doughboy-from-maine/ on February 25, 2024.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. Accessed from https://www.abmc.gov/Meuse-Argonne on February 26, 2024.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. Oise-Aisne American Cemetery. Accessed from https://www.abmc.gov/Oise-Aisne on February 26, 2024.

- TheyServedWiki. Albert Spalding. Access from https://theyserved.fandom.com/wiki/Albert_Spalding on March 3, 2024.

- Wikipedia. Coldstream Guards. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coldstream_Guards on February 28, 2024.

- Wikipedia. Thiepval Memorial. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thiepval_Memorial on March 4, 2024.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 2017. Commemorative Sites Booklet. Accessed from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-Y3_AM3-PURL-gpo82213/pdf/GOVPUB-Y3_AM3-PURL-gpo82213.pdf on February 12, 2024.

- Wikipedia. John J. Pershing. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_J._Pershing on February 12, 2024.

- Potter, C. 1999. National Archives: Prologue Magazine: Vol. 31, No. 2. World War I Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages, Part I. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/gold-star-mothers-1.html on March 4, 2024.

- Potter, C. 1999. National Archives: Prologue Magazine: Vol. 31, No. 3. World War I Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages, Part 2. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/gold-star-mothers-1.html on March 4, 2024.

- Featured Image: WW1 Caskets at Antwerp, Belgium (U.S. Army Signal Corps photo). Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/05/31/world-war-i-exhumed-memorial-day/ on April 4, 2024.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.