On July 21, 1930, President Herbert Hoover signed Executive Order 5298 which consolidated three agencies managing veterans affairs into a single organization called the Veterans Administration (VA). The VA then began to serve the five million veterans of World War I, over 200,000 of which were wounded and/or disabled.1

So, how did the United States serve veterans of previous wars prior to the establishment of the VA? In this month’s Fortitude post, I examine how veterans of the Civil War (1861-1865) were cared for.

The Civil War inflicted an unprecedented amount of causalities never seen before in the United States. Following the war’s conclusion, the Union alone had 1.9 million veterans and Congress needed to act to provide services for soldiers requiring care and places to convalesce from the wounds of war.

Early in the Civil War, Congress passed The General Pension Act of 1862 which provided disability payments based on rank and degree of disability.2 President Lincoln realized that medical care for disabled veterans was solely inadequate. Tens of thousands of Civil War veterans required long-term care for both physical and mental wounds.

Enter The Soldiers Home.

In March 1865, President Lincoln signed legislation to establish the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. This organization was the precursor of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans now had a safe place to receive ongoing treatment for their war injuries and assistance with their disabilities.2

Ultimately, the federal government replaced the word “asylum” with “home” for the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers as they didn’t want to portray the men undergoing care at these facilities as being mentally unstable.2

In 1866, the first site for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, a converted bankrupted resort, opened in Togus, Maine. Over time, these soldier homes expanded to 11 locations.3 By 2019, five of these branches were designated at National Historic Landmarks.4

- Togus, Maine (Eastern Branch)

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Northwestern Branch)

- Dayton, Ohio (Central Branch)

- Hampton, Virginia (Southern Branch)

- Leavenworth, Kansas (Western Branch)

- Sawtelle, California (Pacific Branch)

- Marion, Indiana (Marion Branch)

- Danville, Illinois (Danville Branch)

- Johnson City, Tennessee (Mountain Branch)

- Bath, New York (Bath Branch)

- Hot Springs, South Dakota (Battle Mountain Sanitarium)

Initially these homes were open to Union soldiers who could prove a connection between Civil War service and their injury. By 1884, stays at soldiers home branches expanded to include any honorably discharged soldier or sailor, who could not support himself due to a disability. Their disability did not have to be a service connected.5

The Facilities

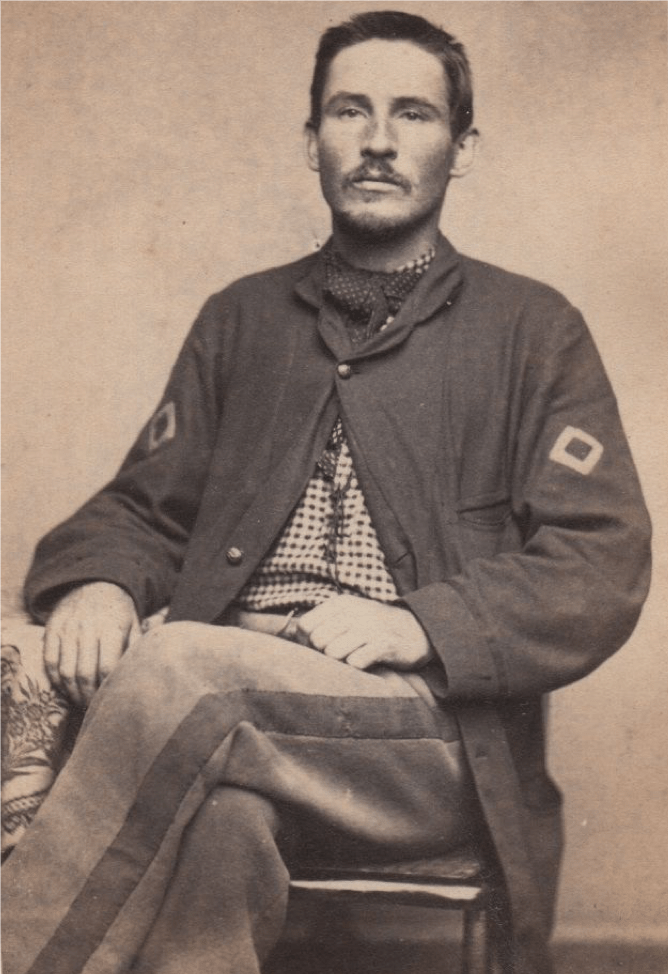

Men living at soldiers homes were issued blue uniforms and informally followed army regulations. Upon admission, each veteran was provided a member number and assigned to a company. A company sergeant led each company. Similar to their active duty days in the Union Army, the men were woken each day with the reveille bugle call. Three other bugle “mess calls” were sounded for meals, with taps being played each night at bedtime.6

At the onset in 1866, soldiers homes served solely as a shelter for disabled Union Civil War veterans. In those early years, branches lacked recreation and leisure activities. Over time, the homes began to offer recreational activities and church services. By 1900, several homes established theaters, libraries, and billiard halls. At the peak of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Civil War veteran residents enjoyed concerts, comedies, melodramas, musicals, vaudeville, and lectures.6

Veterans were provided three meals a day with a varied menu each day. For breakfast they were served items such as boiled ham, corned beef, potatoes, bread, butter, and coffee. Dinner may include roast mutton, vegetable soup, pork loins, boiled beef, peas, green beans, bread, or crackers. Supper was a lighter meal serving mush and syrup, warm biscuits, cheese, and tea.7

Family Connections

If you are a reader of my Fortitude Blog, you know that I enjoy writing about history. Specifically, I value capturing stories of how Spaulding family members intersected those moments in history.

My records search of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers database revealed 70 Spauldings and 22 Spaldings that resided at one of the 11 soldiers home branches. Here are examples of these Civil War veterans:

First Lieutenant Milan D. Spaulding

1stLt. Spaulding of New Hampshire served in Co. C of the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry. Milan enlisted as a private in 1861, was promoted to sergeant in 1864, and then first lieutenant later that year. He saw action in 17 engagements to include the 2nd Battle of Manassas, Gettysburg, and Cold Harbor. Milan was admitted to the Eastern Branch of the soldiers home in Togus, Maine in 1907. He passed away the following year at age 60 of pneumonia.

Sergeant Seely J. Spaulding

Sgt. Spaulding of Vermont served in Co. G of the 2nd Vermont Infantry. He was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia in 1863. Seely was admitted to the Danville Branch of the soldiers home in Danville, Illinois in 1899. He died three years later in 1902 at age 60.

Corporal Joseph A. Spaulding

Cpl. Spaulding of Illinois served three years in the Civil War with Co. I of the 127th Illinois Infantry. In 1929 at age 87, Joseph spent one year at the Western Branch of the soldiers home in Leavenworth, Kansas. After his successful rehabilitation, he went on to live a long life in Kansas passing away in 1943 at age 101.

Private Alonzo N. Spaulding

Pvt. Spaulding of New York served during the majority of the fighting in the Civil War from 1861 to 1864. He was assigned to Co. D of the 84th New York Infantry. In 1911, at age 80, Alonzo was admitted to the Southern Branch of the soldiers home in Hampton, Virginia. He resided there for seven months.

Private John M. Renfro

There’s one last Civil War veteran I’d like to profile. He’s not a Spaulding, but he is my 3rd great-uncle, Pvt. John M. Renfro. John was the younger brother of Mary Esther (Renfro) Spaulding, my 2nd great-grandmother. Pvt. Renfro was assigned to Co. A of the 9th Illinois Cavalry. At age 17, he enlisted in the Union Army in Rock Island, Illinois. In 1895, John, at age 50, spent a brief seven-month period at the Western Branch of the soldiers home in Leavenworth, Kansas. At the time, he was receiving an army pension of six dollars per month. John died in 1916 at age 70.

John’s brothers (my 3rd great-uncles) also served in the Civil War. Older brother William H. Renfro enlisted at age 20 and served with Bat. A of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery. Younger brother George E. Renfro enlisted at age 15 and was assigned to his brother John’s 9th Illinois Cavalry unit. Can you image today’s 15 year old serving in the military during wartime?

End of an Era

As time passed, soldiers home branches began to see a decline in residents as aging Civil War veterans were passing away. By the early 1920s, some branches transitioned into hospitals and medical facilities to care for the World War I veterans. In 1930, Executive Order 5398 established the Veterans Administration (VA) and abolished the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The remaining homes were reorganized as the Bureau of National Homes within the VA.5

Now you have a bit of the history on how our country’s veterans were cared for prior to the founding of the VA. As always, don’t forget to LIKE this post and leave your thoughts in the COMMENT section below.

NOTES

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2021. July 21, 1930: Veterans Administration Created. Accessed from https://department.va.gov/history/featured-stories/va-created/ on December 7, 2024.

- Megelsh, M. 2017. Caring for Veterans: The Civil War And The Present. Accessed from https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2017/02/caring-veterans-civil-war-present/ on December 7, 2024.

- Julin, S. National Park Service (NPS). National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers: Assessment of Significance and National Historic Landmark Recommendations. Accessed from http://npshistory.com/publications/nhl/special-studies/national-home-disabled-vol-soldiers.pdf on December 7, 2024.

- National Park Service. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers National Historic Landmark Study. Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/articles/national-home-for-disabled-volunteer-soldiers-study.htm on December 11, 2024.

- National Park Service. History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/articles/history-of-disabled-volunteer-soldiers.htm on December 11, 2024.

- Plante, T. National Archives. Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1. The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/soldiers-home.html on December 10, 2024.

- National Archives. Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1. The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Typical Menu at the Branch Homes in 1875. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/nhdvs-sidebar2.html on December 8, 2024.

- Featured Image: National Park Service. Ward Memorial Hall, Northwestern Branch, Milwaukee, Wisconsin (1881). Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/articles/history-of-disabled-volunteer-soldiers.htm on December 22, 2024.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nicely done DaleTrust you are enjoying family these days and continue serving our Lord.Last Fall Jan and I were ab

LikeLike