April 9, 2025 marks the 160th anniversary of the end of the American Civil War. That event began a long period of healing and restoration for our Republic. President Lincoln declared an end to slavery by signing the Emancipation Proclamation two years earlier in 1863. But it wasn’t until the passing of the 13th Amendment (Abolition of Slavery) and the end of the Civil War in 1865 that freedom for African Americans began to became a reality.

Efforts to end slavery began prior to the Civil War. In this month’s Fortitude post, I chronicle the work of Rufus Paine Spalding (1798-1886). Although Congressman Spalding did not serve in the Union Army, his efforts to help end slavery were extraordinary as he fought to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

His Career

Rufus Spalding had an impressive career as a lawyer, judge, and congressman in the mid-1800s.1 Two years after graduating from Yale in 1817, he moved west to Ohio to practice law. In 1839, Spalding, a Democrat at the time, was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives serving as Speaker of the House in Ohio in 1841. From 1849 to 1852, Judge Spalding served as an Associate Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court.2

In 1862, Rufus Spalding, running now as a Republican, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives serving Ohio’s 18th congressional district. He served in the 38th, 39th, and 40th Congress from 1863-1869.3 While in Congress, Spalding was appointed to the Standing Committee on Naval Affairs, the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions, and served he as the chairman on the Select Committee on Bankruptcy Law.4

His Politics

Years earlier when serving as a judge in Ohio, Rufus Spalding was a member of the Democratic party. Over time, Spalding found his personal views at odds with the party largely due to the Democrat’s pro-slavery position. Spalding’s position against the spread of slavery to the western territories caught the attention of the newly founded Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party.

In the late 1840s, Free Soil Party leaders invited Rufus Spalding to speak to the party convention in Ohio. Spalding maintained that he was still a democrat, however, in his speech, he was critical of southern democrats and their pro-slavery position. Spalding argued that slavery should not be extended into the American territories and closed his remarks with a call to Free-Soilers to “stand fast” in their beliefs.5

In 1850, Spalding officially left the Democratic Party for the Free Soil Party. His primary motivation was the Democrat’s support of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which in his mind, positioned them as the pro-slavery party. A few years later, the Republican Party was formed via a coalition of the anti-slavery Conscience Whigs and the Free Soil Party.6

The first meeting where “Republican” was suggested as the name for a new anti-slavery party was held in a Ripon, Wisconsin schoolhouse on March 20, 1854. This small schoolhouse was designated a National Historic Landmark for its role in the founding of the Republican Party.6 Less than four years later on November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the first Republican President of the United States.

His Fight

Of the numerous career accomplishments of Rufus Paine Spalding, the most significant to me was his battle against fugitive slave laws.

The Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 were federal laws that allowed for the capture and return of runaway enslaved people within the United States. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 authorized local authorizes to seize and return slaves to their owners and imposed penalties on those who aided in their escape. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 added more provisions regarding runaways and levied harsh punishments for interfering in their capture.7

As an outspoken opponent of slavery, Rufus Spalding rallied other Cleveland attorneys against southern slaveholders traveling North to claim fugitive slaves. In 1859, Spalding represented an Underground Railroad supporter in court. At the trial, Spalding argued that the Fugitive Slave laws were unconstitutional. Despite Spalding’s defense, his client was found guilty of violating the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.2

Two years later, Spalding would again fight the Fugitive Slave Law in court. In 1861, Spalding represented a runaway slave named Lucy who was captured in Cleveland. At the trial, Spalding once again argued that enforcement of the Fugitive Slave laws was both unconstitutional, as well as immoral. Heartbreakingly, Spalding’s defense was unsuccessful, and Lucy was returned to her enslaver. However, the good news (if there could be “good” gleaned from this story) is that Lucy was the last slave to be sent back to the South from Ohio under the Fugitive Slave laws.2

His Loyalty to Lincoln

Congressman Rufus Spalding was a trustworthy supporter of President Lincoln. Spalding made his commitment to the President’s policies clear while serving in Congress by introducing legislation to repeal the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. I suppose that since Rufus was unable to gain freedom for poor Lucy through the courts, he needed to focus his efforts on abolishing the Fugitive Slave Acts once and for all. Spalding’s legislation, passed by Congress in 1864, finally ended the enforcement of these laws requiring the return of runaway slaves to their owners.7

Tragically, President Lincoln wasn’t able to completely witness the fullness of his work to end slavery as he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, just five days after the Civil War ended. The loyalty Congressman Spalding exhibited towards President Lincoln was evidenced through his selection as one of the 22 representatives tasked to meet the President’s remains at his funeral train in Springfield, Illinois.2

His Work In Congress

After the Civil War, Rufus Spalding took a leading role in the Congressional debates over Reconstruction. Many of the measures suggested by Spalding were adopted into the post-war Reconstruction Acts.2

In 1865, Vice President Andrew Johnson, a democrat from Tennessee, assumed the presidency following the assassination of Lincoln. In 1866, Johnson vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, the Civil Rights Bill, and encouraged Southern states not to ratify the 14th Amendment which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States (including former slaves recently freed).8

Over the next two years, serious discussions for the impeachment of a U.S. President began to permeate through Congress for the very first time.

On January 27, 1868, Congressman Rufus Spalding introduced a resolution to have the House Select Committee on Reconstruction conduct an impeachment inquiry into President Andrew Johnson. The President was accused of 11 charges, including the violation of the Tenure of Office Act when Johnson dismissed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who disagreed with Johnson’s Reconstruction policies.2

In late February 1868, the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Johnson of committing high crimes and misdemeanors while in office. This marked the first time a President of the United States was impeached.8

President Andrew Johnson was narrowly acquitted in his Senate trial one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for conviction and removal from office.8 Johnson went on to complete his four-year presidential term ending in March 1869.

His Family Legacy

Congressman Rufus Paine Spalding was named after his father, Dr. Rufus Spalding, the earliest practitioner of medicine prior to 1800 in West Tisbury, Connecticut.9 His middle name came from a prominent New England family on his maternal side via his mother Lydia (Paine) Spalding. Rufus Paine Spalding’s grandfather, David Paine, was a direct descendant of Thomas Paine (1612-1706), who migrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1639 during the Great Puritan Migration.10 The most famous “Paine” of early American history was another Thomas Paine (1737-1809), one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Rufus Spalding married Lucretia Swift in 1822 and they had seven children. After Lucretia died, Rufus married Nancy Pierson in 1859.

Two of Spalding’s sons did their part to preserve the Union and end slavery. Rufus’ oldest son, Lieutenant Colonel Zephaniah Swift Spalding, fought in the Civil War with the 27th Ohio Infantry. Rufus Spalding’s youngest son, Lieutenant George Swift Spalding, also served with the 27th Ohio Infantry in Company H.

Rufus Spalding’s grandson, William Rufus Day (1849-1923), served as a justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1903 to 1922. Prior to his service on the Supreme Court, Day served as Secretary of State under President William McKinley.11

Final Thoughts

It’s safe to say that many Spaldings/Spauldings in America are ancestrally connected. We like to refer to each other as “cousin” no matter how distant that cousin relationship may be. The Spalding ancestry in this post begins with Edward Spalding, a progenitor of the Spalding/Spaulding name in America. Edward Spalding (1601-1669) was Rufus Paine Spalding’s 3rd great-grandfather and my 9th great-grandfather. Rufus descended from Edward and Rachel Spalding’s oldest son Benjamin and I descend from their youngest son Andrew.

I’m thankful I discovered the story of Rufus Paine Spaulding. Conducting the research for this post made me proud of the work of “Cousin Rufus”. Rufus had a remarkable career as a lawyer, judge, and congressman. Better yet, he fought to bring about positive change in our country by defending the human rights of all Americans. Rufus Spalding dedicated his life to putting Lincoln’s words from the Gettysburg Address in action. On that fateful day in 1863, Lincoln so eloquently asserted that the United States was “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal”.

Congressman Rufus Paine Spalding died on August 29, 1886 at age 88. He is buried at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio.

Want to Discover More?

If you enjoy American history and stories of how ordinary, patriotic, and faithful people intersected those moments in history, please consider the following:

SUBSCRIBE to the Fortitude Blog below.

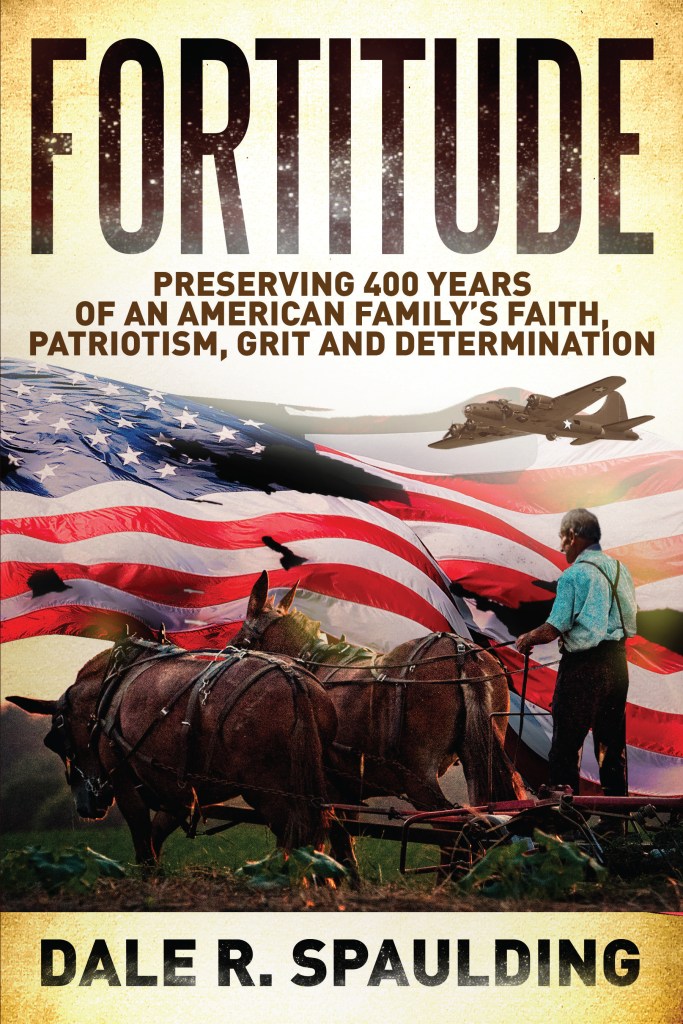

PURCHASE the Fortitude Book HERE.

NOTES

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Spalding (Spaulding), Rufus. Accessed from https://case.edu/ech/articles/s/spalding-spaulding-rufus on January 6, 2025

- Wikipedia. Rufus P. Spalding. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rufus_P._Spalding on January 6, 2025.

- Congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Spalding, Rufus Paine: 1798-1886. Accessed from https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/S000697 on January 7, 2025.

- Still, J. 1948. The Life of Rufus Paine Spalding: An Ohio Politician. Master of Arts Thesis, Ohio State University, p 87.

- Spalding, R. 1847. Oration on the Causes Which Led to Out National Independence, and the True Means for Preserving the Same.

- Wikipedia. Free Soil Party. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Soil_Party on January 6, 2025.

- History.com. Fugitive Slave Acts. Accessed from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts# on January 8, 2025.

- Wikipedia. Second Impeachment Inquiry into Andrew Johnson. Access from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_impeachment_inquiry_into_Andrew_Johnson on January 8, 2025.

- Wikipedia. Little While Schoolhouse. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_White_Schoolhouse on January 7, 2025.

- Still. The Life of Rufus Spalding. pp 3-4.

- Wikipedia. William R. Day. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_R._Day on January 9, 2025.

IMAGES

- Featured Image: Library of Congress. 1861. U.S. Capital Dome Under Construction. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/38th_United_States_Congress#/media/File:LincolnInauguration1861a.jpg on January 9, 2025. Public Domain.

- United States Congress. Biographical Directory. Spalding, Rufus Paine (1798-1886). Accessed from https://bioguideretro.congress.gov/Home/MemberDetails?memIndex=S000697 on January 9, 2025.

- Library of Congress. 1853. Birthplace of the Republican Party. Accessed from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Republican_Schoolhouse%2C_Second_and_Elm_Streets%2C_Ripon%2C_Fond_du_Lac_County%2C_WI_HABS_WIS%2C20-RIPO%2C1-1.tif/ on January 7, 2025. Public Domain.

- Library of Congress. Fugitive Slaw Act of 1850. Accessed from https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/fugitive-slave-act on January 9, 2025.

- Brady, M. 1863. U.S. National Archives. Group Photo of U.S. House of Representatives in 1863. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/38th_United_States_Congress#/media/File:Hon._Schuyler_Colfax,_N.Y._Speaker_of_House_of_Reps_-_NARA_-_528686.jpg on January 8, 2025. Public Domain.

- Findagrave.com. Rufus Paine Spalding gravestone. Accessed from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/22526/rufus_paine_spalding on January 8, 2025.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Interesting article Cousin Dale I can hardly believe we have not gotten together for over a year. Lets try in the next couple of weeks. Perhaps meet at the Stockyards in Ft Worth? I have attached an article from Ancestry and it has portions from the Spaulding Memorial but written better. Maybe when you’re short of material you could use it. in your blog. David 810-577-6444

LikeLiked by 1 person