As we enter 2026—the year marking the 250th anniversary of the United States—I’m reminded of the remarkable stories that shaped our nation’s beginning. In past posts of The Fortitude Blog, I’ve explored many facets of the American Revolution, including: Sons of the Founding Fathers, An Unsung Hero: The Story of Joseph Warren, Sons of Liberty and History’s Forgotten Marksman: Joseph Spaulding at Bunker Hill.

In this month’s Fortitude post, I’m once again returning to the era of the American Revolution—this time to uncover the stories of American patriots taken prisoner by the British. Staying true to the recurring theme of this blog, which highlights family members woven into moments of history, I’ll be sharing the accounts of several Spaldings and Spauldings who were captured during the Revolutionary War.

American Revolution POW Stats

During the Revolutionary War, an estimated 20,000 Americans were held POWs.1 The over 11,000 American POW deaths during the American Revolution far exceeded those 6,800 killed in action.2,3

The British did not officially acknowledge American combatants as prisoners of war until late in the conflict, viewing them instead as traitors. Conditions in British-held prisons were oftentimes harsh, marked by severe neglect and starvation. This mistreatment of American captives was likely intended to discourage other “rebels” from supporting the American cause.

The Prison Ships

During the American Revolution, the British held American POWs in prison ships anchored in New York, Charleston, Savanah, Norfolk, and Halifax, Nova Scotia.

From 1776 to 1783, British forces occupying New York City used abandoned or decommissioned warships anchored offshore to imprison captured soldiers, sailors, and civilians. Thousands of American prisoners perished aboard these ships. Many died from disease, malnutrition, and harsh conditions. Those who died were sometimes thrown overboard, while others were taken ashore and buried in shallow graves.1

The HMS Jersey was a former Royal Navy ship converted into a prison hulk in 1779. Moored in Wallabout Bay, New York—now part of the Brooklyn Navy Yard—the ship earned the grim nickname “the floating hell.”

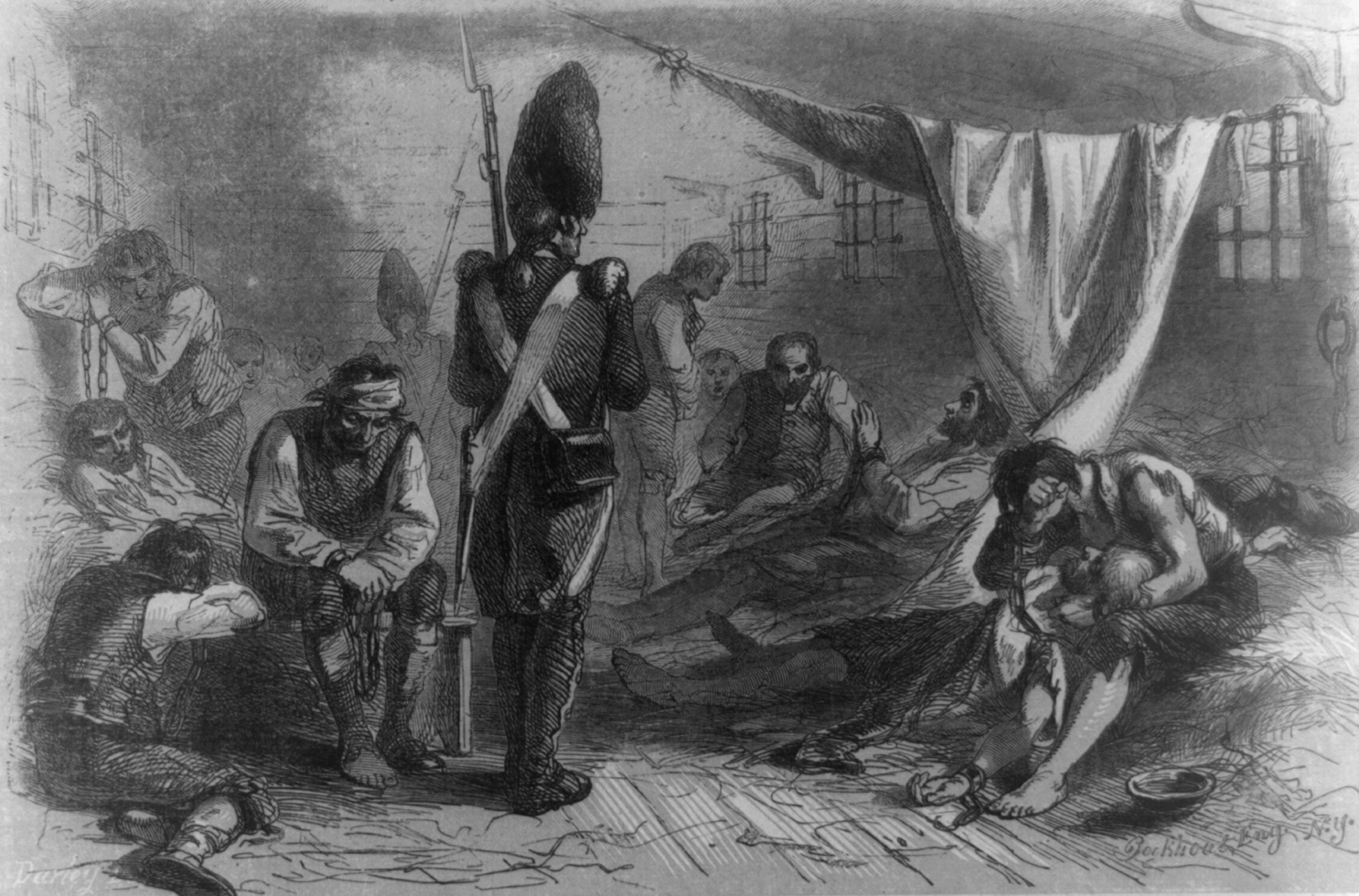

Conditions aboard the Jersey were horrific, as illustrated by the sketch shown in the featured image of this post. Originally designed to hold 400 men, it was often overcrowded with more than 1,000 prisoners. Around a dozen men died daily from disease—including smallpox, dysentery, typhoid, and yellow fever—as well as from starvation and brutal treatment.4

Over the course of the war, thousands of American prisoners died aboard the Jersey. As late as 1841, the bones of many of these victims were still being found on the shores of Wallabout Bay, in and around the Navy Yard.5

The POWs

Regular readers of The Fortitude Blog know that when I delve into history, I often highlight the Spaldings or Spauldings (my surname) whose lives intersected those pivotal moments. Today, I’m sharing the stories of several family patriots who were held as POWs during the American Revolution.

Enoch Spalding

Corporal Enoch Spalding served in the New Hampshire militia during the American Revolution. He was captured by the British and imprisoned aboard the notorious HMS Jersey in New York. Corporal Spalding’s name is on a list of 8,000 men held prisoner on the Jersey that was compiled by The Society of Old Brooklynites in 1888.6

I was unable to locate any records of the final fate of Corporal Enoch Spalding.

Dr. Noah Spalding

Dr. Noah Spalding, a Connecticut physician, enlisted as a surgeon during the Revolutionary War. He was captured and imprisoned aboard the Lord Stanley, a British prison ship anchored in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Dr. Spalding died while held on that vessel. It’s likely that, even in captivity, he used his medical skills to aid fellow patriots before ultimately succumbing to the brutal conditions on board.7

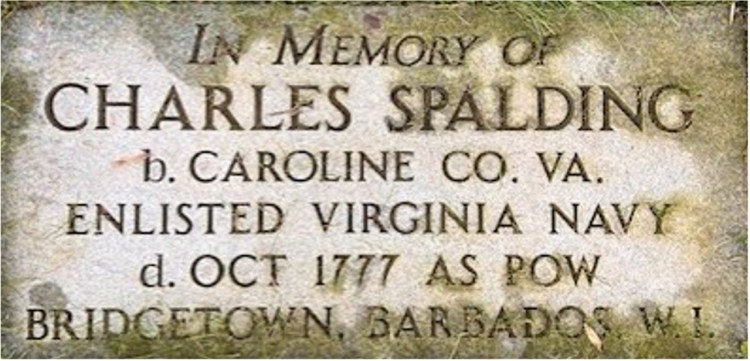

Charles Spalding

Private Charles Spaulding enlisted in the Continental Marines in Virginia in 1776. He served under Alexander Dick, a Captain of Marines.

Captain Dick’s Marine company, serving aboard the four-gun Continental naval brig Mosquito, was captured in June 1777 by the twenty-gun British Royal Navy ship HMS Ariadne and the vessel was later burned. A brig is a two-masted, square-rigged ship known during the American Revolution for its speed.

In a letter written from the Forton Jail in England in May 1778, Captain Dick wrote:

“I was taken by the Ariadne on the 4th of June last [1777], in the brig Musquito, belonging to the state of Virginia having on board part of my company belonging to the first Virginia regiment of provincials. The officers belonging to the vessel, and myself, were sent to England and committed to this jail. My men were sent to jail in Barbados.”8

—Captain Alexander Dick, Continental Marines (1778)

In a Southern Campaign American Revolution Pensions Statement in 1784, now Major Alexander Dick certified that Charles Spalding enlisted with him in 1776 and was taken prisoner with him in June 1777 onboard the Musquito Brig. Major Dick stated that he heard Charles Spalding died about four months later in the Barbados Goal [Jail].8

In a post-war pensions interview, Charles mother, Mildred Spalding, testified that her eldest son enlisted in 1776. She had never seen or heard from him since he went to sea with Captain Alexander Dick—and she has heard, and believes, he was dead. Additionally, Sergeant William Coleman, who also served under Captain Dick, made an oath that he saw Charles Spalding die in the Barbados Goal [Jail] in October 1777.9

There’s a memorial marker honoring Charles Spalding at the Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.

Phineas Spaulding

Phineas and Sarah Spaulding raised their five children on a farm in Panton, Vermont near Lake Champlain. Multiple battles were fought on and around Lake Champlain during the Revolutionary War.

In October of 1777, Phineas and eleven other civilians of Panton and surrounding Addison County were taken prisoners and held aboard a British ship on Lake Champlain. Phineas was tasked with processing the animals brought on board for food. One day he spotted an opportunity to escape and jumped onto a small boat moored alongside the vessel. As he paddled to shore, he was spotted by a British solider and ordered to return. Knowing they would soon fire upon him, Phineas jumped into the water and swam safely to shore amid a hail bullets.10

A year later in November 1778, a British force of several vessels returned to the region on Lake Champlain and burned every house in Panton but one. Phineas Spaulding’s farm house was destroyed that day. Two of Phineas’ sons were taken prisoners. He, however, escaped to Rutland, Vermont, where he died not long thereafter.11

George and Philip Spaulding

The two sons of Phineas Spaulding captured that day were Phillip, age 24, and George, age 17. Along with other civilian prisoners, they were taken north to Canada.

Like their father, Phineas, both brothers had a remarkable knack for escape. They managed to break free, and Phillip—along with several others—traveled through the wilderness for twenty-one days before finally reaching the Connecticut River at Newbury, Vermont. Philip then enlisted and served throughout the remainder of the Revolutionary War.12

George Spaulding, the younger brother, was recaptured and placed in irons. The British offered him his freedom on the condition that he first travel to Great Britain. During a port stop in Ireland, he went ashore—only to be seized by a press-gang, a group authorized by the British government to forcibly impress men into service in the Royal Navy.

I was unable to locate any records as to the final fate of George Spaulding.

Closing Thoughts

Countless stories of patriotism emerged during the founding of the United States and the struggle of the American Revolution. These accounts of sacrifice, hardship, and heroism deserve to be rediscovered and preserved for future generations. We must remember the people—and the experiences—behind the freedoms we enjoy today. Sadly, many stories, including those of American patriots held as POWs during the American Revolution, have been lost to time.

I am grateful for the opportunity to help bring just a few of these stories back to light in this month’s Fortitude post.

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below.

NOTES

- Marsh, A. 1998. National Park Service. POWs in American History: A Synopsis. Accessed from https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/pow_synopsis.htm on November 27, 2025.

- The Veterans Museum at Balboa Park. Revolutionary War (War for Independence) 1775-1783. Accessed from https://veteranmuseum.net/research-revolutionary-war/ on November 27, 2025.

- Daugherty, G. 2020. History.com. The Appalling Way the British Tried to Recruit Americans Away from Revolt. Accessed from https://www.history.com/articles/british-prison-ships-american-revolution-hms-jersey on November 27, 2025.

- History.com. 2010. The HMS Jersey. Accessed from https://www.history.com/articles/the-hms-jersey on November 24, 2025.

- Dandridge, D. 1910. American Prisoners of the Revolution. Chapter XXV: A Description of The Jersey. Accessed from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7829/7829-h/7829-h.htm on November 24, 2025.

- Ibid, Appendix A: List of 8,000 Men Who Were Prisoners On Board The Old Jersey.

- Spalding, C. The Spalding Memorial: A Genealogical History of Edward Spalding of Virginia and Massachusetts Bay and His Descendants. (Illinois: American Publishers Association, 1897), 197.

- Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters. Pension Application of Alexander Dick R13751. Accessed from https://revwarapps.org/r13751.pdf on November 27, 2025.

- Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters. Virginia documents pertaining to Charles Spalding VAS4598. Accessed from https://www.revwarapps.org/VAS4598.pdf on November 27, 2025.

- Spalding, C. The Spalding Memorial, 115.

- Wiggly Goat Farm. 2025. Revolution: Patriots, Hardship, and Survival on the Frontier. Accessed from https://wigglygoatfarm.com/revolution-patriots-hardship-and-survival-on-the-frontier/ on November 29, 2025.

- Spalding, C. The Spalding Memorial, 200.

- Featured Image: Library of Congress. 1855. Interior of old Jersey prison ship, in the Revolutionary War. Accessed from https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a09150/ on December 1, 2025.

- Image. Library of Congress. 1906. The Prison Ship “Jersey”. Accessed from https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99472279/ on December 1, 2025.

- Image. Van Powell, W. 1974. CNS Mosquito and CNS Fly. Accessed from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CNS_Mosquito_and_CNS_Fly.jpg on December 1, 2025. Public Domain.

- Image: Amos, A. 2025. Charles Spalding Memorial Marker. Photo courtesy of Cave Hill Cemetery, Louisville, Kentucky.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.