NOTE from Dale: I launched the Fortitude Blog in 2021, and this month, I’m thrilled to introduce my first guest blogger. Clare Cory is the great-great-granddaughter of Civil War veteran, SGT Dewitt C. Spaulding. SGT Spaulding kept a personal diary during the Civil War from August 1861 to December 1864. Here’s SGT Spaulding’s compelling story of survival from his great-great-granddaughter Clare after her family visit to the Andersonville, Georgia POW site.

Prisoner of War, Andersonville, Monday, July 4 – A citizen of a free America and yet not free. The 88 years of our independence. A civilized country, an enlightened age . . and still heathen. Here we are in free America supposed to be a model for all Nations. And here exists suffering no one can portray; helpless and defenseless and while in this state shot down for the most trifling offense. Hand-cuffed with a 60# ball and chain. Gagged. Feet in the stocks. Beaten. Tortures of every kind. And on all sides we can hear the cry of give one bread; only a small piece of bread for I am starving. I am dying. The lifeless forms of many are carried to the south gate, thrown in a pile. There they are corded like wood into wagons and taken to their grave – a large ditch where they are thrown in on top of the others (after being stripped of all their clothes). They are covered with the dust out of which they came; there to rest until the final resurrection. Oh Thou Judge of All. Have mercy on all who have suffered here. Oh Christ – thou who agonized in the Garden – have mercy on them. May their suffering here in part atone for their sins. Of those who cause us such suffering we would say as thou didst: forgive them for they know not what they do. Weather warm. Rain PM.

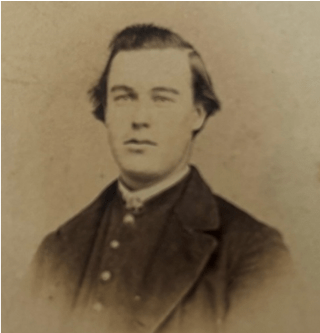

Sgt Dewitt C. Spaulding, Union Army (1864)

Sgt DeWitt Clinton Spaulding, Company G, Michigan 8th Infantry, penned these haunting words while incarcerated at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Enlisting with the Michigan 8th at age 18 in August, 1861, his unit was known as the “Wandering Infantry.” They fought in many battles, including Antietam where DeWitt was promoted to Sergeant for bravery exhibited in battle.

Early in May, 1864, the Michigan 8th was engaged at the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia. On the afternoon of May 6, after hours of intense fighting, DeWitt stopped to help a wounded soldier and became separated from his Regiment. In the dense brush, he lost his way and mistakenly ran into Rebel lines where he was captured by the Confederates. Thus began the greatest test of his young life; seven months as a Prisoner of War marked by extreme hardship, deprivation and life-threatening illness.

As was common for many Civil War soldiers, DeWitt faithfully maintained a diary of his wartime experiences. Beginning on August 15, 1861 and concluding on December 20, 1864, he left his descendants a remarkable account of his years as a Union soldier. His writings have inspired family trips to battlefields, including Antietam and the Wilderness, and most recently, a trip to the Prison Stockades of Andersonville and Florence, SC.

Arriving at Andersonville this past May, four of DeWitt’s direct descendants met with Teri S., a Park Guide with the NPS, who provided a great deal of historical information and context. A visit to Andersonville has much to offer, including the National Prisoner of War Museum, which honors POWs of all wars, the Civil War-era Prison site, and the Andersonville National Cemetery.

During our tour, we learned that prisoner exchanges between the Union and Confederacy had decreased significantly in 1863 because Confederate forces refused to treat black prisoners the same as white prisoners. Without the opportunity for exchange, captured soldiers needed to be secured. This resulted in an urgent need to construct prison camps. Both sides were unprepared to accept responsibility for large numbers of POWs and Union and Confederate prison camps alike became places of desperate suffering and death.

A notorious place from the time of its inception in the spring of 1864, Andersonville had the highest death rate of any Civil War prison, with 29% of prisoners dying during captivity. Of 45,000 POWs who arrived in Georgia, 12,920 died while incarcerated. By the time DeWitt arrived, he would have heard of the horrors of Andersonville, although it seemed nothing could prepare him for what he encountered.

An exact reproduction of the North Gate, the area through which all prisoners entered Andersonville, is situated on the location of the original. As we began our tour, we saw the railroad stop where POWs disembarked and marched a short distance to the heavily guarded Stockade. Cannons were pointed toward the gate and hundreds of Confederate soldiers were camped outside the prison walls. Guards were stationed in towers along the top of the Stockade. At least 15 plantation bloodhounds chased down any escapees.

Our guide informed us that we undoubtedly walked in our ancestor’s footsteps as we came up the road from the railroad tracks, traversed a sloping hill and proceeded toward the North Gate. We paused to read DeWitt’s diary entry, then entered through the outer gate and into a holding area. Here, new arrivals were examined for smallpox. Aware that an outbreak of the disease could prove lethal to all, the Confederates immediately quarantined any detainees who presented with smallpox symptoms. As a result, only 45 men died of smallpox at Andersonville.

Walking in DeWitt’s footsteps 160 years later, I found myself profoundly moved. As he entered through the North Gate and discovered the wretched conditions of the prison, he had no idea whether he would survive nor who would claim victory in the bitterly fought war. At only 21 years of age, he found himself a POW in his own country, facing conditions that would break the heartiest of men. He wrote:

“I must bow to my fate and pray God that day is not far distant when I shall once more be free. “Free” – how that word sounds to nice ears. Can I ever be free again? Oh God, thou alone knowest.“

Although Andersonville is now a peaceful place, our Guide informed us that it wasn’t that way during the torturous summer of 1864. The large population of prisoners made Andersonville the fifth largest city in the Confederacy. Teeming with activity, a Confederate Camp surrounded the Stockade and their campfires burned all night. Guarding the Stockade required 800 men per day. By the end of June, Andersonville held 25,000 prisoners. Although the original Stockade construction included 16.5 acres, the prohibited area of the deadline and several acres of mud surrounding the foul creek running through the camp left only 8.5 acres of livable space. Each man had about 2.07 square feet to call his own.

Walking the site, I tried to imagine a medium-sized city of POWs confined to a space that was designed to hold half the number. Sewage from the Confederate camp and grease from the bake-house just outside the prison walls flowed into the creek before it entered the prison. The same creek was used by prisoners for drinking, washing and latrines. Sounds of the sick and dying filled the air. Some Catholic priests were allowed into the prison to administer last rites, often crawling into dirt holes to deliver the prayers.

A cart entered the camp daily containing pitiable food rations for the prisoners and the same cart exited carrying the bodies of those who had died the night before. The odor emanating from the Camp was legendary, said to fill the air for miles around. During that summer, rain poured relentlessly, creating a muddy mix of raw sewage around the Camp because many men suffered from diarrhea and dysentery and were too weak to make it to the latrine area. With little opportunity to wash and virtually no soap available, one can only imagine the smell generated by thousands of filthy men. DeWitt wrote that, “The article that we call soap in the North isn’t known here so I had to get along without it.” Our guide said that the prison camp quieted down only in the hours just before dawn.

In June, Confederate General John Winder took command of Andersonville, arriving with an interesting backstory. During the War of 1812, his father, General William Winder, led his troops to defeat, thereby allowing the British to burn Washington. This crushing event made a deep impression on John, who was only 12 years old at the time. He eventually entered West Point, vowing to restore his family’s name. General Winder surely desired accolades for his management of Andersonville, although he failed miserably in this endeavor. He died in 1865, before he could be held responsible for the tragedy that had occurred under his watch.

Although there are many claims of escaped prisoners from Andersonville, our Guide stated that there were only 33 successful escapes from the Prison, which was defined by the soldier returning to his Regiment. No one escaped from inside the Stockade and all who eluded capture had been working outside the prison walls. Within the Camp, the main causes of death were diarrhea, scurvy and dysentery. For those admitted to the Camp Hospital, gangrene stole the most lives. August 9 was the date on which the most prisoners perished in a single day, and 3,000 men died during that month. During that same period, more than 30,000 prisoners languished at Andersonville.

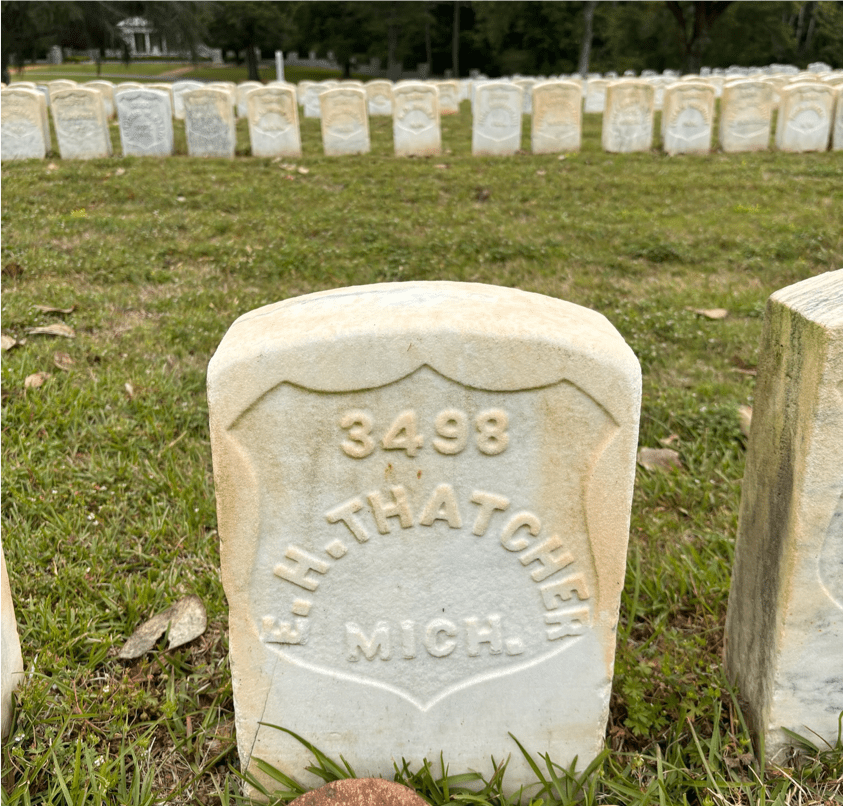

Dorance Atwater, a 19-year-old POW, worked in the prison hospital and kept a secret ledger of prisoner deaths, which later allowed for the identification of gravesites at the Andersonville National Cemetery. Following the end of the War, young Atwater and Clara Barton returned to Andersonville and meticulously identified the final resting places of thousands of soldiers, such that headstones could be placed which listed a name and regiment.

We learned that this was not the case at the Florence Stockade, where we traveled following the Andersonville visit. Along with thousands of other POWs, DeWitt was transferred to Florence in September after Union General Sherman captured Atlanta. Fearful of a prisoner uprising, the Confederates quickly relocated thousands of POWs to South Carolina. The Stockade wasn’t yet complete when they arrived, and they spent weeks camped in a field under heavy guard. Most who arrived in South Carolina were already severely weakened by disease and starvation, resulting in more deaths. At Florence, 2,500 Union soldiers are buried in mass graves, their names lost to history.

DeWitt’s words continue to inspire and one passage has bought comfort during my own challenges with cancer. On June 3 he wrote:

“Just thirty days a prisoner in their infernal regions and yet if I have lived one month why cannot I live another? As the old saying is, while there is life there is hope.”

Following his transfer to Florence, DeWitt mentioned Union POWs who agreed to take the Oath of the Confederacy as a way to obtain work and food. He refused. I wish I could say I would make the same choice as my great-great-grandfather but the truth is that I don’t know what I would do, especially after months of starvation. Two days after his 22nd birthday, DeWitt wrote the following:

“Many more are putting down their names but they will have to starve me awhile longer to get me to bow to their miserable Confederacy.”

As we concluded our visit to Andersonville, our Guide, who had analyzed DeWitt’s writings, took us to the area where she believed he had resided during his excruciating months as a POW. The four of us gathered in that place where he had suffered so much, looking across the field that had once held the despair of thousands of men. I wished that I could travel back in time to whisper in the ear of a courageous and honorable young man that he would regain his freedom, live to a ripe old age and that his sacrifice and service would be remembered for generations to come. Hundreds of us would owe our very existence to his will to survive. And, although it might seem impossible to believe while a prisoner, his descendants would return 160 years later to the place of his life’s worst agony, grateful for his enduring legacy.

Note: On behalf of our family, we extend our sincere appreciation to Teri S. and all staff members and volunteers working at the Andersonville National Historic Site. Their dedicated efforts to preserve history connect us across generations and guide us to a better future.

Clare Cory, Guest Blogger for the Fortitude Blog

Final note from Dale

Thank you again Clare for sharing your family’s story of walking in the footsteps your ancestor, and Civil War hero, Sgt DeWitt C. Spaulding.

If you enjoy history and stories of ordinary, faithful, and patriotic people like Dewitt Spaulding, who did extraordinary things, please check out my book Fortitude HERE. If you’d like to receive the monthly Fortitude blog posts directly to your email, please subscribe below.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wow! I’m consistently blown away by the history and legacy of your family. It makes me want to be a better person. Thank you so much for sharing this with us. God bless you brother! This article was very well written. Brought a tear to my eye. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dale,

Please pass our thanks to Ms. Clare Cory for an interesting read and, to her and Sgt Dewitt Spaulding, job well done!

-Jay Parker-

US Army Veteran

LikeLiked by 1 person

Our oldest grandchild lived with us and attended Blackshear, GA Elementary; his first grade teacher was the excellent Kathy Paul.

A solitary marker, easily missed by most in nearby deciduous woods, states that thousands of union troops were forced to walk there from Andersonville for relocation. A fact not anyone seems interested in remembering. I thought you might be interested to know that. Keep up the great work, Dale and Nancy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dale started this family pilgrimage. His appreciation of our unique country, our struggles, and our successes, is an example for us all. Our National Park Service has done much to preserve this heritage.

LikeLiked by 1 person