NOTE from Dale (Fortitude Blogger): I’m excited to introduce my cousin Karen Aumond, our guest blogger for this month. In this post, she chronicles her 2024 journey to Washington D.C. to hold a piece of family history that is 170 years old. It was an opportunity of a lifetime – enjoy the story!

I am an only child and, maybe due to my lack of siblings, I have been interested in my family history for as long as I can remember. My parents and grandmother would tell me stories and I have tried to fill in the blanks where I can. I joined Ancestry.com and have an extensive tree there, along with my DNA. I have also submitted DNA to 23andMe.

When my father, Richard Carlson, and his brother Robert Carlson got together in later years, there was frequent conversation about their family history. I remember hearing that their mother, Catherine Battles (Spaulding) Carlson, was deaf. They also talked about an ancestor, Addison Spaulding, who made artificial legs.

My family connection to Addison:

- Addison Spaulding: 3rd Great-grandfather

- William Sidney Spaulding: 2nd Great-grandfather

- Arthur Addison Spaulding: Great-grandfather

- Catherine Battles (Spaulding) Carlson: Grandmother

- Richard Harold Carlson: Father

- Karen Lu (Carlson) Aumond: Me!

The Story

I didn’t think much more about that artificial leg story until I read Dale Spaulding’s book Fortitude: Preserving 400 Years of an American Family’s Faith, Patriotism, Grit and Determination. In the book, Dale details how in February 1848 Addison Spaulding lost his leg when he was bringing a cart filled with muck (dirt, rubbish and waste matter) to his home. The cart got stuck and as he was trying to free it, the axel broke and the cart tipped over on him. Addison was a mile from home and couldn’t free himself. He was alone and recognized that he must get back to the farm and get help for his injured leg. He was able to reach his shovel and then dig enough to get out from under the cart. Somehow, he was able to unhook the horse he had brought along and he rode it home. His leg was so badly fractured that the only option was amputation. On February 3, 1848 his leg was amputated below the knee.

It made me realize how fortunate our family is that Addison Spaulding had that will to survive. Just getting back to the farm was a feat in itself – but surviving an amputation was also quite miraculous. Back then they used chloroform for the surgery and there were no antibiotics to deal with the infection that likely was present from the muck. What grit Addison showed. This story prompted Dale Spaulding to name his book “Fortitude”!

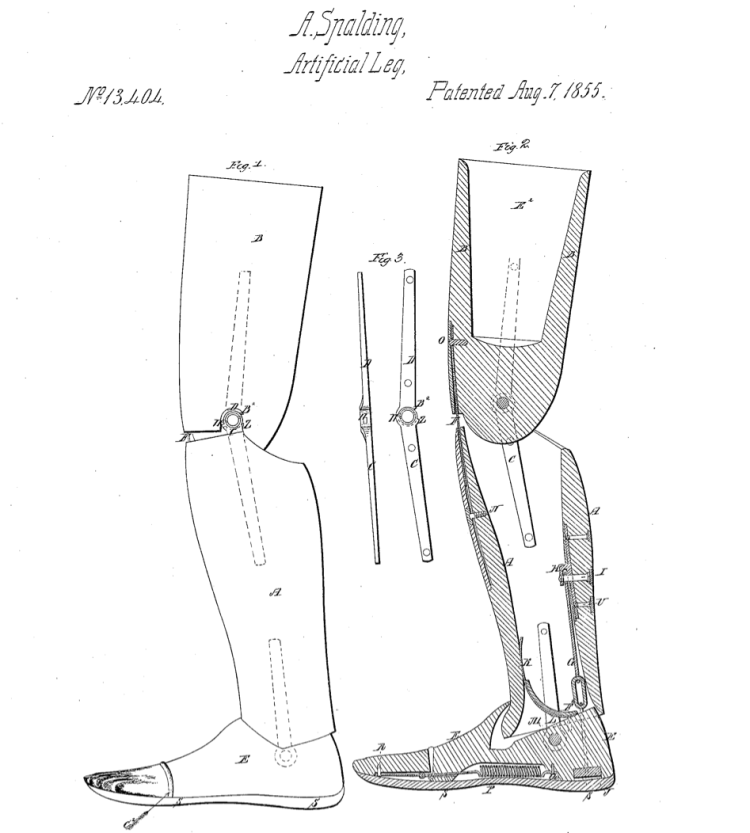

After recovering from the surgery, Addison Spaulding (a farmer) made himself an artificial leg. Seven years later, on August 7, 1855, he filed for, and obtained, an artificial leg patent. When pondering this, I surmised that the old adage, “necessity is the mother of invention” played a large role in Addison becoming a patented designer for artificial legs. You can tell by the patent information that he has first-hand knowledge of the benefits and drawbacks associated with many of the previous designs. The model the artificial leg Addison submitted with his patent application is held at the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

My Quest to Hold History

In August 2024, my husband and I received word that a dear friend’s burial at Arlington Cemetery was scheduled for October 24th. There was no doubt that we would be there. It was then that we decided to spend 5 days in D.C. in order to do some sightseeing in our Nation’s Capital. This time also corresponded with my birthday on October 23rd.

While planning this trip, I recalled the information in “Fortitude” about Addison Spaulding’s patented leg being in the Smithsonian. I went to the Smithsonian website and saw a page stating, “Someone from my family has donated an object to the museum. Is it available for viewing?” I went to the Smithsonian website and found this FORM to request a viewing of the artificial leg.

I sent the following message:

Hello, I will be visiting the Museum of American History on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 23rd. My 3rd great grandfather, Addison Spaulding, patented an artificial leg that I believe is held by the Museum. It is patent number 13404, Patented August 7, 1855, Medical. I would very much like to view this piece if that is possible. Thank you in advance, Karen Aumond.

There is a disclaimer on the Smithsonian form that they “are very busy and may not have time to respond to any requests.” I wasn’t really expecting to get a response. Then, to my surprise on Oct 7th, I received an email from Dr. Katherine Ott, Curator, Division of Medicine and Science. She explained that the Spaulding patent model was kept in an offsite storage location and she would try to arrange for it to be brought into her office in the Smithsonian American History Museum. Two days later Dr. Ott replied indicating the artificial leg would be brought downtown to the Smithsonian from “their collection of warehouses in the suburbs”.

My husband and I arrived at the American History Museum and looked around until 3:00pm, the time that Dr. Ott arranged for us to meet. I was filled with anticipation and excitement as we perused this wonderful museum. If you’ve never been to this museum, it’s really special and so worth a visit. When 3:00pm came we went to the reception desk and I called Katherine Ott. She said she would be right down. I was a bit nervous, but Dr. Ott was very gracious and welcoming and immediately made me feel at ease.

Dr. Ott said, “follow me” and took my husband and I up to the fifth floor, which required an elevator key card to enter. She explained that they had done some research on the Spaulding leg and presented me with a file of information about the patent and how the artificial leg came to them.

She indicated that the leg is actually a scale model (not a full-sized artificial leg) that was required to be submitted with each patent application. She also provided me with the full patent application, which she obtained from the Library of Congress. I noted the drawing must have been done by someone other than Addison Spaulding, as the his name on the top of the drawing was misspelled as Addison Spalding (without the “u”). The document was very detailed and included information about what made this invention better than previous ones. She also showed us information about how the Smithsonian obtained Addison’s patent model in 1978.

In later researching the patent process, I found an article in American Heritage Magazine that described the beginnings of American patents.1 Seven weeks before the 13 original states ratified the Constitution, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph became the Patent Commission. When they opened for business on April 10, 1790, they immediately established the requirement that a working model of each invention, done in miniature, be submitted as part of the application. The problem was that the government was soon overrun with models of all types and sizes and they were paying to store them without even knowing what was where!

This old patent model collection was decimated by four fires over the years. It is a wonder that the artificial leg designed by Addison Spaulding even made it to the Smithsonian so that I could see it!

Dr. Ott explained that the Smithsonian Museum bought the Spaulding artificial leg on March 20, 1978 as part of a group of nine artificial leg models from New York Auctioneer O. Rundle Gilbert.

The yellow note in the photo states: “Certified to be the original model, From: Mr. and Mrs. O. Rundle Gilbert’s Collection of Original United States Patent Models, 1790 – 1890, Garrison, NY.”

According to an article in The New Yorker, in 1941, O. Rundle Gilbert bought just about all of the existing models that inventors had submitted to the U.S. Patent Office in the 19th century for $2,500.2 It’s estimated there may have been 100,000 models. Mr. Gilbert was an auctioneer based in Garrison of Putnam County, NY. He hoped to make money selling these models at a much higher price than he had paid. He tried selling them to the Smithsonian Institution but they had all the models they wanted. Fortunately for us, the Smithsonian did eventually buy this model!

An article from the American Orthotic & Prosthetic Association entitled “O & P in the 1800s states:3

“Prior to the Civil War in the United States, prosthetics and orthotics were relatively unknown,” according to an early document titled, “History of Prosthetic-Orthotic Education.” This document goes on to explain, “A physician who specialized in disorders of the bones and joints usually employed an apprentice who would accompany him on his rounds and assist him in his office in applying splints and fitting limbs as needed. This was the beginning of the practice of orthopedics and of orthotics in America.” The first U.S. artificial limb facility is cited as opening in 1840 in New York.

Both Bly and Palmer artificial legs were purchased by the Smithsonian in the same purchase order from O. Rundle Gilbert as Spaulding’s artificial leg. B. Frank Palmer, revised and improved the function of his prosthesis, and received the first patent for an artificial limb in the United States in 1846. Palmer eventually operated limb manufacturing facilities in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.3

Spaulding’s Improvements

Interestingly, Addison Spaulding stated in his 1855 patent application that: “the surface of deer skin stuffed with hair and attached toe bottom of the foot, described with the invention patented by B. Frank Palmer, August 17, 1852, as such will not retain any elasticity when used but will cake together as hard as the wood, of which the leg is composed.”

Addison Spaulding’s patent application included the following wording:

The artificial leg has the following improvements over other legs that were studied and rejected:

- Improved knee spring for throwing forward the lower portion of the leg in order to lessen the liability for persons falling

- The ankle spring for swinging up the forward portion of the foot or other turning point at each step of the operator

- India rubber spring attached to a chain at the heel of the foot to allow the leg a slight elasticity when placed on the ground and tipped forward by the operator, to prevent the shock upon the cords and nerves in the stump of the natural leg

In the patent application, Spaulding also stated: “I form a recess to receive the trunk of the leg when amputated above the knee. When amputated below the knee, the wood in the lower portion of the top should be removed so as to allow the trunk or stump of the human leg to project downward onto the leg A (Note: Calf area on patent drawing), bringing the joint of the human knee on a line with the joint of the artificial one.”

This is significant because Addison’s amputation was below his knee. The leg he designed for patent could be used for either an above the knee amputation or a below the knee amputation.

The Civil War – A Desperate Need for Artificial Limbs

The need for artificial limbs reached a new high after the Civil War began in April 1861. With some 70 percent of Civil War wounds affecting the limbs, amputation quickly became the treatment of choice in battlefield surgery. A primary amputation was easier, faster, and—with a mortality rate of ‘only’ 28 percent—safer than other treatment options.” The carnage associated with the Civil War, resulted in more than 60,000 amputation surgeries, according to historical records.

Civil War amputees began to make their own prostheses – much as Addison Spaulding had done when his leg was amputated. “Many of these men, not being able to return to their former trades, and being unsatisfied with the substitute limbs given them by the government, either went to work in existing limb facilities to master a new trade or made improvements in their limbs and opened their places of business . . . to sell their improved version to the amputee public,” reports the History of Prosthetic-Orthotic Education.4

Dr. Ott could not find any record of Addison making full-scale artificial legs or having another company manufacture or sell any of his design. The Smithsonian’s description of the patent states: “Patent model for Addison Spalding, “Construction of Artificial Legs,” U.S. Patent 13,404 (Aug. 7, 1855). Spalding, a resident of Lowell, Massachusetts, manufactured legs of this sort for a dozen years or so.”5

Additionally, the 1860 Census shows Addison’s occupation as “Patented Leg Manufacturer”. It appears that Addison Spaulding continued making artificial legs for amputees during and after the Civil War. Two of Addison’s sons fought in the Civil War, with one losing his life.

Moving into the Smithsonian Storage Area to see the Spaulding Leg

Next, Dr. Ott asked if we were ready to see the leg. I enthusiastically replied, “yes, please!” She took us across the hall to another locked room. She unlocked the door and there were multitudes of storage cabinets. A few were lowered with table tops on them. We stopped at one of those. Katherine unlocked a cabinet that held the box with the model leg submitted by Addison Spaulding and brought it to the table. It was in a square box.

Katherine very diligently put on rubber gloves and opened the box. Then she lifted the leg up and out. The actual Spaulding model was finally right before my eyes! We took some time discussing the different features such as the hollowed out top and the ball joint in the knee which can be removed for legs amputated below the knee.

I was surprised by how heavy it is given that it was not full scale. I thought how difficult it must have been to wear the full-scale leg – and how far prosthetic devices have come, due in large part to these early pioneers.

I was especially captivated by the foot. It had rubber on the bottom to cushion steps. It also had toes carved into it. I can imagine this aesthetic was added to make the wearer feel better as it makes the feet appear to match when barefoot. I was curious as to how heavy the leg was so Katherine handed me the leg in the box.

I experienced so many emotions as I saw the 1855 artificial leg in person that was designed by my 3rd great-grandfather. I felt a renewed connection to my family’s history. I was proud that my ancestor had contributed to the improvement of a medical device that continues to benefit so many today.

I am extremely proud that this piece is in the prestigious Smithsonian Museum of American History. Dr. Ott emphasized to us that she worked for the American people and that this was “OUR” museum. What a great honor to feel so connected to this Institution.

After I returned home, I sent an email to Dr. Ott thanking her for taking the time to arrange transferring the Spaulding leg from storage in Maryland to the Smithsonian Museum of American History so that I could see it. She said that it was her honor and that she would be glad to show it to any other Spaulding relatives – with advance notice, of course.

FINAL NOTE from Dale: On behalf of the many descendants of Addison Spaulding (and all lovers of history), thank you Karen for making this trip to the Smithsonian to view Addison’s artificial leg model. Thank you for capturing your story of “holding history” – we sensed the joy of your experience through your words. What a great day!

NOTES

- Hogan, Donald. Unwanted Treasures Of The Patent Office. American Heritage. Volume 9, Issue 2, February 1958. Accessed from: https://www.americanheritage.com/unwanted-treasures-patent-office

- Trillin, Calvin. U.S. Journal: Garrison, N.Y. Jackpot. The New Yorker. January 7, 1974, p. 52. Accessed from: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1974/01/07/u-s-journal-garrison-n-y-jackpot

- O&P in the 1800s. American Orthotic & Prosthetic Association, p. 7. Accessed from https://www.aopanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/0AOPA-Directory_2017-FINAL-VERSION.pdf

- Ibid, p.8.

- Smithsonian. National Museum of American History. Artificial Leg. Accessed from https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_211063

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for sharing your adventure with us, Karen. What a great story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful story. I am so impressed with the treatment you received from Dr. Ott. As a historian myself, I am always impressed with how far archivists are willing to go to assist me. I love Dr. Ott’s statement that she works “for the American people and that this was OUR museum.” Lesson learned: Never be afraid to ask about what’s hidden behind the locked doors!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks David – you are spot on. We have so much expertise available to us at museums across our country to help with our research. Professionals like Dr. Ott are ready to help us discover more – we just need to ask.

LikeLike