Throughout human history, few things have remained as personal and powerful as the signature. Whether written with ink, stamped with a seal, or typed with digital encryption, a signature stands as a testament to identity and agreement. But where did the idea of signing your name come from and how did it evolve?

In this month’s Fortitude post, I dive into the fascinating history of signatures and show you the marks made by my ancestors from over 300 years ago.

Ancient Beginnings

Long before paper and pens existed, humans found ways to mark their identity. The oldest known signature dates back to a Sumerian scribe who etched his name into a clay tablet around 3100 BC in ancient Mesopotamia.1

The ancient Egyptians also left their marks. High-ranking officials used hieroglyphs or seal impressions to identify themselves on papyrus scrolls and stone monuments.2 Similarly, the Chinese began using seals made of stone, ivory, wood, or jade as early as 1600 BC.3 These seals served as confirmation of an individual’s mark.

Personal Marks

As civilizations advanced, the need for more sophisticated methods of identity verification grew. In Medieval Europe, literacy was rare, so personal marks and wax seals became the signature of choice. Seals were pressed into hot wax using intricately carved rings or stamps to serve as a form of identification.

The seal wasn’t just decorative—it carried legal weight. A sealed letter from someone in authority could authorize military action, grant land, or settle a dispute. During the Late Middle Ages, forgery of a seal was a serious crime, akin to counterfeiting today.4

Since the 1600s, it’s often been wrongly assumed that anyone who “made their mark”, instead of signing their name, was illiterate. But that’s not necessarily true. In the 17th and 18th centuries, individuals were sometimes instructed to make a unique mark—rather than write their name—on legally binding documents, when witnesses were present. In some cases, such as when a person was gravely ill when signing their last will and testament, making a mark may have been all they were physically able to do.

Handwritten Signatures

The Renaissance Period marked a turning point in the history of signatures. With the invention of the printing press in the 15th century and the gradual rise of literacy, handwritten signatures became more widespread. During the 17th and 18th centuries, signing one’s name was common on contracts, letters, and decrees.5

John Hancock’s signature, one of the most famous in American history, emerged during this period. Hancock’s bold signature on the Declaration of Independence in 1776 is so iconic that “giving your John Hancock” became a euphemism for signing one’s name.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, laws in many countries began to formalize the legality of signed documents, cementing the importance of the personal signature.

Ancestral Signatures

I did some digging into old ancestral documents such as wills, letters, and government forms to uncover the signatures of my ancestors from over 300 years ago. Here’s what I found:

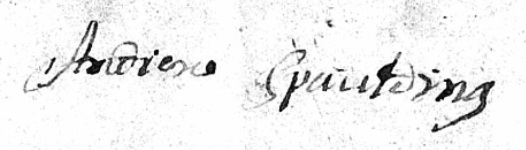

Andrew Spaulding (1653-1713): My 8th Great-Grandfather, Andrew, was a farmer in Chelmsford, Massachusetts. He served as a deacon in the First Parrish Church. To safeguard the European settlers in the area, 19 garrisons were formed. Andrew led the Great Brook Garrison consisting of 15 men. Andrew also served his community as Constable of Chelmsford. In the image below, note that the “A” between Andrew and Spaulding is labeled as “his mark”.

Andrew Spaulding II (1678-1753): My 7th Great-Grandfather, Andrew II, was a teacher in the Chelmsford Grammar School in the early and mid 1700s. He and his wife Abigail had a large family of 12 children. Like his father, Andrew II served as a deacon in the First Parish Church of Chelmsford, Massachusetts.

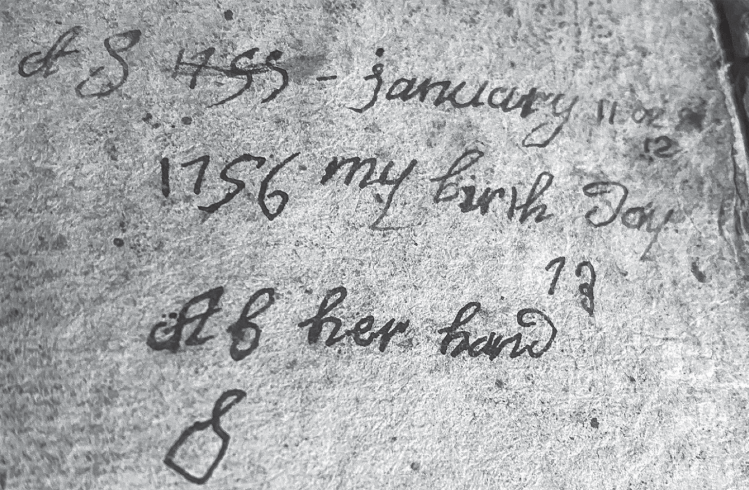

Abigail Spaulding (1682-1768). My 7th Great-Grandmother, Abigail Spaulding, was the wife of Andrew Spaulding II. In the image below from a book she owned, Abigail is recording her birthday each year. First, you see her initials “AS” at the top left of the image. The year 1755 is crossed out indicating that year has passed. In the following year, she writes, “1756 my birth day 73” and the words, “AS her hand.” Below Abigail’s handwritten words, you see a unique shape that appears to be a woman’s brush. This was likely Abigail Spaulding’s mark.

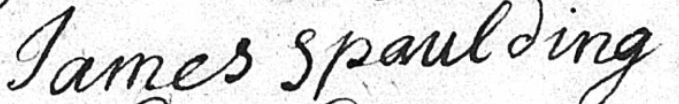

James Spaulding (1714-1790): My 6th Great-Grandfather, James, and his wife Anna, were “Parents of Patriots”. All four of their sons served in the American Revolution. I found James’ signature on a court probate record from the estate of his father Andrew Spaulding II. Read the story of James and Anna Spaulding’s boys, in Sons of Liberty, HERE.

Benjamin Spaulding (1738-1810): My 5th Great-Grandfather, Benjamin, served in the American Revolution. Captain Spaulding led a company of New Hampshire militia that joined with the Continental Army at West Point, New York in 1780. I obtained Benjamin’s signature from his last will and testament recorded in 1806.

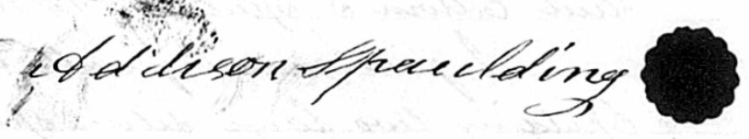

Addison Spaulding (1807-1874): My 3rd Great-Grandfather, Addison, was a farmer in Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1848, he lost his leg in a farming accident. He then built an artificial leg for himself and ultimately obtained a patent for his device in 1855. Two of his sons served in the Civil War, only one returned home. I found Addison’s signature on his last will and testament recorded in 1873. Read the story of Addison Spaulding, The Overcomer, HERE.

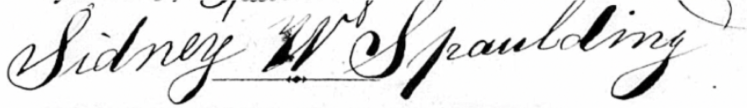

William S. Spaulding (1832-1909): My 2nd Great-Grandfather, William, was a blacksmith and first to bring my family line west from New England to the state of Illinois in the 1850s. It appears that William went by his middle name, Sidney, during his life. His signature below from the final settlement of his father’s estate is signed Sidney W. Spaulding. However, in Illinois, his marriage license, Rock Island newspaper obituary, and gravestone all reflect his birth name, William S. Spaulding. Read the story of William, An American Blacksmith, HERE.

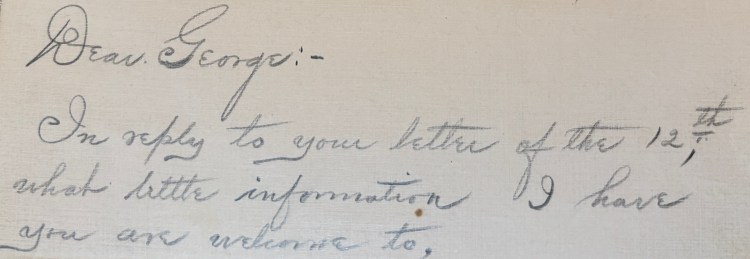

Arthur A. Spaulding (1862-1947): My Great-Grandfather, Arthur, worked on the railroad during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Beginning as a locomotive fireman, he fed the engine’s fires by shoveling coal into the train engine’s firebox. Ultimately, he worked his way up to locomotive engineer. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to locate Arthur’s signature, but I do own a hand-written letter he wrote on the topic of family history to his son, George (my grandfather), in 1931.

George A. Spaulding (1891-1978): My Grandfather, George, spent his career in sales. First with the Moline Plow Company in Illinois, then in the steel business with the Bliss & Laughlin Steel Company. By the end of his career, he was promoted to vice president and selected as one of the company’s directors. I found George’s signature on his World War II draft registration card. Although George didn’t serve on active duty, as he was too old, two of his sons (my uncles) both deployed overseas during World War II.

Unfortunately, the exquisite handwriting of many of my ancestors didn’t pass down to me. My signature is basically illegible. I’ll just blame it on the permanent stiffness in my right hand after breaking it playing pickleball.

Final Thoughts

The signature has traveled a long and fascinating road—from ancient clay tablets to today’s encrypted digital files. The signature is an indication of commitment, a reflection of identity, and a foundational component of society. While technology may change how we sign, the reasons behind why we sign, remain the same.

Challenge: Please take some time to discover the signatures of your ancestors. In the comment section of this post below, tell us the time period of the oldest signature of an ancestor you were able to find.

Continue the Story: If you enjoy history and appreciate stories about how ordinary, faithful, patriotic and hard-working people intersected those moments of history, please check out my book, Fortitude: Preserving 400 Years of an American Family’s Faith, Patriotism, Grit and Determination, HERE.

NOTES

- The Grizzly Labs. 2020. The Signature: A Brief History. Accessed from https://blog.thegrizzlylabs.com/2020/11/history-of-signatures.html on June 15, 2025.

- Smart History. The British Museum. Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Overview. Accessed from https://smarthistory.org/ancient-egyptian-hieroglyphs/ on June 17, 2025.

- China Online Museum. Chinese Seals. Accessed from https://www.comuseum.com/culture/seals/ on June 17, 2025.

- Cambridge University Press. 2023. 7 – Counterfeiters, Forgers and Felons in English Courts, 1200-1400. Accessed from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/expectations-of-the-law-in-the-middle-ages/counterfeiters-forgers-and-felons-in-english-courts-12001400/ on June 17, 2025.

- Felsenthal, J. 2011. Slate Magazine. Give Me Your John Hancock. Accessed from https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2011/03/when-did-we-start-signing-our-names-to-authenticate-documents.html on June 17, 2025.

- Featured Image: Aritao, Lawrence. 2020. Holding a fountain pen with a journal below. Accessed from https://unsplash.com/photos/person-writing-on-white-paper-GlbW3FzMSFE on June 23, 2025. Free to use under the Unsplash License.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This was very interesting, Dale. Thanks for sharing it.Terry Babcock

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Terry – appreciate it.

LikeLike

You’re right, Dale, those signatures were exquisitely written. We should all have such well-crafted signatures. But, alas, we’re too absorbed with pickleball. Makes me wonder what our descendants will think about that: Will such thoughts be sweet as a gherkin or sour as a dill?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anyone interested in continuing the Spalding collection? For sale to best offer. I have done what I could to keep the name alive and now it is someone else’s turn.

Marti Spalding: 978-452-6184

LikeLike