Before I jump into this month’s post, I’d like to take a moment to celebrate a little milestone. This month—November 2025—marks four years since I launched The Fortitude Blog! I’m deeply grateful to my readers and subscribers who have been along for the ride and shared in the stories and history we’ve explored together over these past four years.

Now, on to this month’s post.

In your travels, have you have ever wandered through a colonial-era graveyard in New England? If so, you likely noted the striking imagery marking those weathered old gravestones. Skulls, winged hourglasses, crossed bones, and weeping willows – these mysterious symbols seem strange to our modern eyes.

Colonial gravestones, dating in the 1600s and 1700s, were more than mere markers of life and death – they portray the community’s beliefs regarding faith, mortality, and the hope of eternal life. Decoding these symbols reveals an intimate look into the spiritual and cultural worlds of America’s early European settlers.

In this month’s Fortitude post, I’ll describe the most common symbols that adorn these gravestones and provide examples of the markers of my Spaulding ancestors that lived in colonial New England beginning in the 1600s.

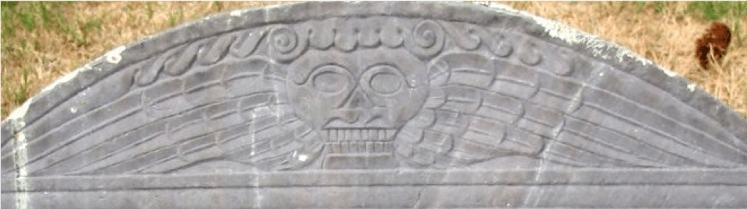

The Death’s Head

Among the most recognizable and dramatic symbols on colonial gravestones is the death’s head: a skull, often accompanied by hollow eyes and a row of teeth. The skull-with-wings variation, often called a “winged death’s head,” added an important dimension – the hope of the soul’s flight to heaven.1

Alongside the carved symbols, colonial gravestones often contained epitaphs to include information on the deceased along with words of warning, consolation, or praise.

For the Puritans and other early colonists, death was not something to avoid thinking about. It was part of daily life, given the mortality rates of the New World. Some gravestones of this era contained the words “memento mori” – Latin for “remember you must die.”2 The death’s head grave marking was a blunt reminder for the living of their own mortality and the urgency of living a God-fearing life.

Andrew Spaulding (1653-1713)

My 8th great-grandfather, Andrew Spaulding, was a Deacon at the First Parrish Church and Constable of Chelmsford, Massachusetts. He was the son of Edward Spalding, the first to bring my family name to the colonies in the early 1600s. Andrew is buried at the Forefathers Burying Ground in Chelmsford.

HERE LYES THE

BODY OF DEACO

ANDREW SPOLDIN

AGED 59 YEARS

AND 3 MONTHS

WHO DEPARTED

THIS LIFE MAY

THE 5TH 1713

You likely noted that Deacon Andrew Spaulding’s last name was incorrectly spelled as “Spoldin” – not even close, right? Unfortunately, errors like these were commonplace on colonial-era gravestones.

“We sometimes wonder why the people of these past days ever bought some of the gravestones; those that have a rather hideous death’s head, or are carelessly done with three or more rows of teeth, bad spelling, poor spacing, and made perhaps on a poor piece of slate which broke under the stonecutter’s tool.”3

—Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1927)

Hannah Spaulding (1654-1730)

My 8th great-grandmother, Hannah Spaulding, was the wife of Deacon Andrew Spaulding. She was the daughter of Henry Jefes and Hannah (Births) Jefes of Billerica, Massachusetts. Hannah is buried at the Forefathers Burying Ground in Chelmsford.

Here lyes ye Body of

Mrs. Hannah Spauldin

Wife to Deacon Andrew

Spauldin: Who died

Janry ye 21 1730 in ye

77 Year of her Age.

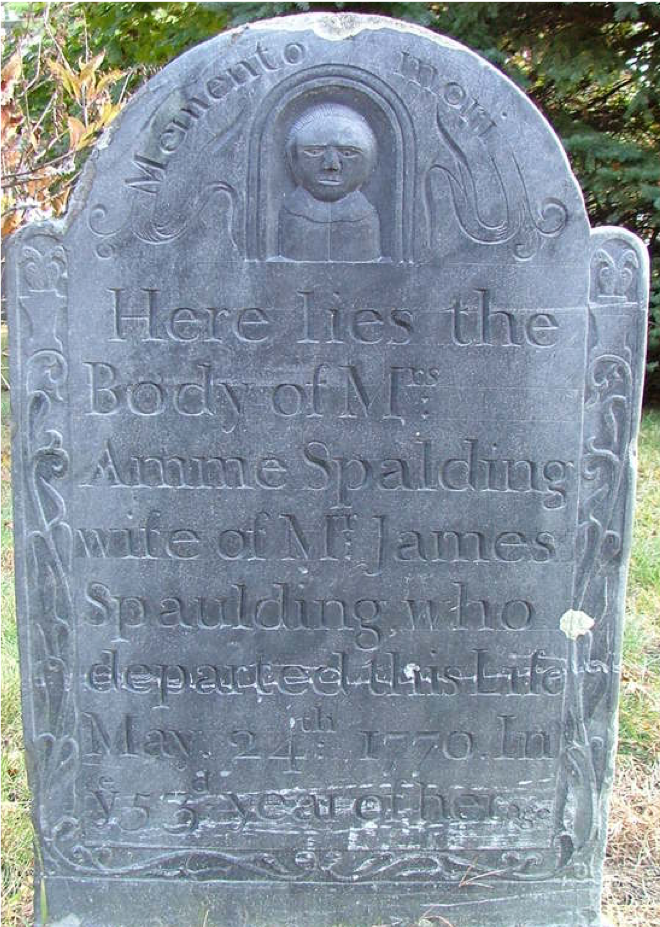

The Soul Effigy

By the late 18th century, gravestone imagery began to soften. A new motif emerged – the “soul effigy” or “angel face”. These tranquil, softer faces often resemble a child or infant, framed with graceful wings that replaced the harsher skulls of the previous century.4

This transition reflects the changes brought on in the 1740s with The Great Awakening led by evangelists George Whitefield and Johnathan Edwards. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, The Great Awakening made one’s relationship with God more personal by fostering a sense of spiritual conviction of personal sin, the need for redemption, and salvation through faith in Jesus Christ.5

Soul effigies still reminded people of the reality of death, but with a hopeful promise of eternal life for the faithful. The message was still very clear – death was certain, but there is comfort in the certainty of eternal life for the faithful.

Andrew Spaulding II (1678-1753)

Like his father, my 7th great-grandfather, Andrew Spaulding II, was a Deacon at the First Parrish Church of Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Andrew II is buried at the Forefathers Burying Ground in Chelmsford.

Here Lies Buried

The Body of

Decn Andrew

Spaulding Who

Departed This

Life Novem ye 7

1753 In ye 75th

year of his Age

Abigail Spaulding (1682-1768)

My 7th great-grandmother, Abigail Spaulding, was the wife of Deacon Andrew Spaulding II. She was the daughter of Jacob Warren and Mary (Hildreth) Warren of Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Abigail is buried at the Forefathers Burying Ground in Chelmsford.

Here lies the

Body of Mrs Abegal

Spaulding wife of

Deacon Androw Spaulding

who departed this

Life May 12th 1768

In the 86th

Year of her

Age

Anna “Amme” Spaulding (1717-1770)

My 6th great-grandmother, Amme Spaulding, was the wife of James Spaulding. James’ gravestone did not survive the test of time. Amme was the daughter of Joseph Underwood and Susannah (Parker) Underwood of Westford, Massachusetts. Amme’s four sons, Benjamin (my 5th great-grandfather) and his three brothers, James, Silas, and Phineas, all fought in the American Revolution. Read their stories in Sons of Liberty HERE. Amme is buried at the Hillside Cemetery in Westford, Massachusetts.

Note in the epitaph on her gravestone the spelling of Spalding (without the u) for Amme, and Spaulding (with the u) for her husband James. Wonder how the family felt about that when they visited Amme’s grave?

Here lies the

Body of Mrs

Amme Spalding

wife of Mr James

Spaulding who

departed this Life

May 24th 1770. In

ye 53d year of her age

Other Gravestone Symbols

Soon the gravestone image of the hourglass, sometimes depicted with wings, became popular. Time, like death, was unavoidable, and the sands of life were always slipping away.6

To colonial Americans, the hourglass warned that life was fleeting. The winged version sharpened that message even further as “time flies.” In an era where disease, accidents, and war could claim lives without warning, the hourglass symbol urged the community to get right with God before it’s too late.

In the 19th century, America’s gravestones changed once again. Early markings listed above were being replaced by urns, weeping willow, crossed bones, flowers, leaves, orvine patterns, open books (the Bible), or other religious symbols (praying hands or finger pointing up).7

Gravestones were expensive, often the second-most costly item in a funeral after the coffin. As a result, images carved on the gravestone of a lost loved one were deeply personal. This array of new images gave family members multiple options to express their grief, faith, and remembrance.

The Stonecutters

It’s important to remember that gravestone symbolism was also shaped by the stonecutters themselves. Colonial gravestones were hand-carved by local artisans whose skills and artistic choices impacted what people experienced in the graveyards.

Among early Puritan gravestone carvers, certain artisans developed recognizable styles. The “Stone Cutter of Boston,” whose name has been lost to history, and Joseph Lamson (1658–1722) stood out as particularly accomplished. Though Lamson began as the apprentice, their evolving designs suggest a shared creative journey – one in which the student eventually surpassed the master.8

By the mid-1800s, these ornate gravestone symbols simply vanished in my ancestral line. For example, my 4th great-grandparents, Jesse and Winifred Spaulding died in Vermont in the 1850s. They had large headstones, but no decorative symbols – just names and dates. The same was true for my 3rd great-grandparents, Addison and Nancy Spaulding, who died in Massachusetts in the 1870s. Was it because the gravestone artisans of the 17th and 18th centuries no longer performed their craft? Or was it simply a financial decision for my ancestors?

Final Thoughts

Today, colonial graveyards serve as outdoor museums of early American beliefs. The gravestones remind us that our ancestors faced death with a multifaceted mix of fear, faith, and hope. They bear witness to the skill and creativity of early American artisans who turned simple headstones into profound works of art.

Visiting a colonial burying ground and examining gravestone symbols is a powerful experience connecting us with the thoughts and emotions of ancestors long ago.

So the next time you wander through an old cemetery, take a moment to throughly examine the gravestones. The words and symbols, though weathered by centuries of wind and rain, still have much to teach us about life and death.

“Therefore we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day.For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.“

—2 Corinthians 4:16-18

NOTES

- Leavitt, L. The Tufts Daily. 2020. Little Bit of History Repeating: Gravestone Depictions. Accessed from https://www.tuftsdaily.com/article/2020/10/little-bit-of-history-repeating-gravestone-depictions on August 4, 2025.

- Palmer, B. Curationist. 2022. Memento Mori: The Importance of Death for a Virtuous Life. Accessed from https://www.curationist.org/editorial-features/article/memento-mori:-the-importance-of-death-for-a-virtuous-life#on August 4, 2025.

- Forbes, H. Gravestones of Early New England and the Men Who Made Them 1653-1800. (Massachusetts: The Riverside Press, 1927), p. 14.

- Henderson, C. 2024. Family Tree Magazine. Gravestone Symbols and Their Hidden Meanings. Accessed from https://familytreemagazine.com/cemeteries/hidden-meanings-gravestone-symbols/ on August 3, 2025.

- History.com. Great Awakening. Accessed from https://www.history.com/articles/great-awakening on August 4, 2025.

- Dan TDJ. Medium. 2024. The Symbolism of the Winged Hourglass on 18th-Century Tombstones. Accessed from https://devantlamort.medium.com/the-symbolism-of-the-winged-hourglass-on-18th-century-tombstones-dd730b221a8f# on August 4, 2025.

- Hartley, P. Family History Daily. The Hidden Meaning of Grave Marker Symbols Explained. Accessed from https://familyhistorydaily.com/genealogy-resources/grave-marker-symbols/ on August 4, 2025.

- Diaz, D. 2019. New England Graves: Phipps Street Burying Ground. Accessed from https://anarmchairacademic.wordpress.com/2019/04/23/new-england-graves-phipps-street-burying-ground/ on August 3, 2025.

- Featured Image: Spaulding, D. 2021. Forefathers Burying Ground. Taken behind First Parrish Church of Chelmsford, MA.

Discover more from Fortitude

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you as always for making interesting what wouldn’t have seemed to be. And yes… time flies and only in one direction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much information. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you send me this blog post so I can add some helpful comments?

marti >

LikeLike

Dale, This newsletter was so interesting. And now you and Nancy have a kids book too?! You two amaze me! Congratulations to the both of you! Hope you’re doing well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks brother – appreciate that!

LikeLike